A Guest Post by Aaron Michael Ritchey

I recently read Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, and it’s about dreams, or more precisely, the following of dreams, the wretched path that narrows, and the splendor of the vision. As you follow your dreams, Paulo writes, it’s important to notice omens along the way.

Omens, as in messages from the gods, or God, or the big bright Whatever in the sky. In pursuing my own writerly dreams, I’ve had omens, I guess, maybe. I’m a hugely dramatic man, and the only omens I care about are either engulfed in flames or splattered with the blood of sacrificial virgins. I want impossible-to-ignore omens, dammit, crows that caw my name, and if I don’t get the cawing, it doesn’t count.

As you can guess, I’m disappointed much of the time. I can easily discount every single omen I’ve been gien on my writer’s journey. And I can point out to you, in exquisite detail, the omens my fellow authors have been given. Sure, the crows caw their name, but not mine.

Let’s talk about my first good omen. My dad had a friend who worked for the Modern Language Associations, you know, the MLA. They were to the English language as the KGB was to communism. Nobody messed with the MLA. My dad gave his friend a story to read, and she loved it and praised my talent. It was an omen. Or was it? She was my dad’s friend. I was sixteen and fragile and she was probably just sparing my feelings. Screw that omen, it doesn’t count.

In high school my stories were chosen to be in the literary magazine. That’s an omen, right? No, I had to vote for my own stories in order to win, and Pat Engelking always beat me. No omen for me!

A year after college, I finished my first novel. I gave it to a friend. He cried reading it. Omen, yeah? No, that first book was so bad that my wife couldn’t read it. And I dedicated it to her! The crows sat in silent scorn in the trees outside my house.

I wrote an epic trilogy after that, and my audience doubled to friends loving my work, but it still doesn’t count. I still wasn’t published.

Then? Eight books later, my lucky thirteenth book I’d written, The Never Prayer, not only was a finalist in a writing contest, but a publisher wanted to publisher it! Omens galore! Hide the virgins, the dagger is thirsty tonight!

I didn’t win the contest, and the publisher went under. As in glug, glug, glug. Going down three times, and coming up twice. No omens.

But my second book, er, fourteenth book, Long Live the Suicide King, found a publisher, and I got a strong Kirkus Review! Not just strong, glowing, put on your sunglasses. That’s GOT to be an omen. Kirkus, son, they don’t mess around.

But I’ve read other books that got glowing Kirkus Reviews, and those books were iffy. Some downright bad. Not. An. Omen.

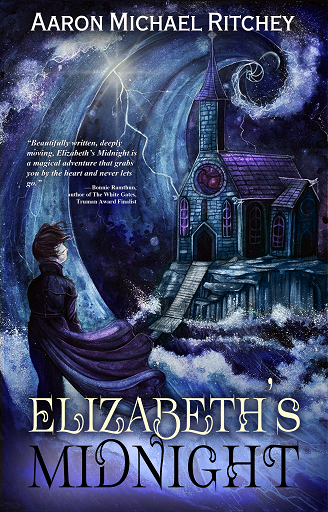

But what about my last book I published, Elizabeth’s Midnight? Omens? Another good Kirkus Review (Indie, so it doesn’t count), more good reviews on Amazon (blah, blah, blah), and even fan mail. Am I rich and famous? Am I hanging out with Lady Gaga? Do editors read my work and say, “Sorry, man, I’d like to edit it, but it’s too damn good.”

But what about my last book I published, Elizabeth’s Midnight? Omens? Another good Kirkus Review (Indie, so it doesn’t count), more good reviews on Amazon (blah, blah, blah), and even fan mail. Am I rich and famous? Am I hanging out with Lady Gaga? Do editors read my work and say, “Sorry, man, I’d like to edit it, but it’s too damn good.”

No. No omens.

So yeah, that’s me. I’m a small-minded, ungrateful, hateful little man. I’ve never had a literary agent. I’ve never been signed on by the big six, or five, or one. I’ve not been chosen by the elite.

For me, and this is only for me, my omens come in small packages, and I have the freedom to recognize them as omens, or discount them and be the lead kazoo player in my own pity-party band.

For me, I have to work to believe in my omens. Omen #1? My wife loves my books and is willing to spend money on them. That, my friend, is a bush on fire. She’s a frugal, level-headed sort of woman, and if she didn’t think I could make it, we wouldn’t be spending the benjamins.

Omen #2? My daughters read Elizabeth’s Midnight and loved it. If my wife is frugal with our money, my daughters are even cheaper with their literary praise.

Omen #3? I’ve had fan moments, where actual people, who have read my book, looked at me in wonder. I’ve gotten fanmail. Not a lot, but what I have gotten? Astounding.

The last omen? The only omen that really counts? I WANT TO WRITE BOOKS. I want to write a lot of books. If the good Lord didn’t want me writing, he wouldn’t have given me the desire to create stories. That is the crow cawing my name.

I have been chosen because I am choosing, choosing to write books and get them published, by any means necessary.

Omen enough for me.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Aaron Michael Ritchey is the author of The Never Prayer and Long Live the Suicide King. Kirkus Reviews called his latest novel, Elizabeth’s Midnight, “a transformative tale for those who believe in magic and in a young girl’s heart.” In shorter fiction, his G.I. Joe inspired novella was an Amazon bestseller in Kindle Worlds and his steampunk story, “The Dirges of Percival Lewand” was part of The Best of Penny Dread Tales anthology. He lives in Colorado with his wife and two ancient goddesses of chaos posing as his daughters. Visit his website at www.aaronmritchey.com.