As writers, we hear a lot about the importance of world building. This is especially true of fantasy, and is pretty much required for epic fantasy. It also is helpful in other genres, such as sci-fi or westerns. Building worlds is a multi-layered endeavor, and done properly results in a rich and varied setting that can be so compelling that the setting can essentially become another character.

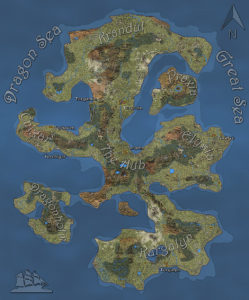

One of the best ways to start down the path toward such a compelling setting is to start with a map. Maps force you to make decisions about things that will, or should, have direct impact on your characters’ journeys both figuratively and literally.

One of the best ways to start down the path toward such a compelling setting is to start with a map. Maps force you to make decisions about things that will, or should, have direct impact on your characters’ journeys both figuratively and literally.

How far apart are the different areas your characters will travel? How long will it take them to get there? Will they have specific travel needs? What is the terrain like? Will they cross mountains, sail across seas, encounter impossible-seeming obstacles? Creating a compelling map is as much a creative endeavor as writing the story itself. But it does exercise different skills than writing.

There are excellent map creation tutorials on the internet. I’ve played around with some of the techniques, and used some of the programs. Long before I drew my map for my debut War Chronicles novels, I was drawing maps by the notebook-full for my role-playing adventure gaming sessions.

This article isn’t going to cover the technical details of map making though. Instead, I want to focus on the part of map making that is frequently overlooked and under-appreciated. Even the most beautifully rendered and creative map won’t help your story if all it does is lay out the landscape. For the map to be as useful to you, and as compelling to your readers, as possible, it should present your world as dynamic and alive. So how do you do that?

Here is what I do after the terrain has been laid out and rendered, more or less in the order that I do it.

- I work out the drivers of the world’s economies. That is driven by very basic decisions about things that are not immediately visible, but drive the evolution of cities, nations and geopolitics. These include answering the following questions for each area of the map:

- What crops are grown?

- What minerals are available?

- What is the climate?

- What is the seasonal weather?

- What are the obstacles to easy travel?

- Next, I work out the location of the major cities. That is based on the following questions:

- What proximity to navigable trade routes?

- What is the population density of the area?

- What will the climate and weather allow?

- What technological level are the inhabitants?

- Then I work on the religions of the world, asking the following:

- What are the major religions of the world?

- Where are they based?

- What are their religious teachings and dogma?

- How powerful are they?

- Then I work out the geopolitics, based on more questions:

- What are the natural boundaries based on terrain?

- What sort of political system controls the area?

- How do trade goods move through the world?

- What is the history of each nation?

- Finally, I focus in on the current time, and ask the following questions:

- What are the current political squabbles?

- Which nations are allied with each other?

- Which nations have long-held relationships?

- Which nations are at war, and why?

- Which nations care about the current wars, and why?

- And finally, I use all the above information to create what I call the “Movers and shakers list.” Which answers the following questions:

- Who are the rulers of the dominant nations?

- Who are the forces behind the thrones?

- Who are the business leaders, and what are their goals?

- Who leads the religious organizations?

In the end, my “map” ends up as a singular diagram, and a pile of notes describing each area individually, and what are the paths that people, goods and ideas travel in the world.

These notes are not generally large and complex. A few sentences answering each of the questions above is usually sufficient. Then, as the story is unfolding, I can use those notes to inform the narrative, providing logical rationale for why two cities are in conflict, or why a rich merchant wants to hire mercenaries, or just about any other question that needs to be answered to drive the plot forward in a plausible manner, which simultaneously peels back more and more layers of the world for the reader. Also, as the characters travel from place to place, I will know what sort of culture they are encountering, what local dynamics drive the behavior of the local populace, and who they need to seek out, or avoid, to be successful in achieving their goals.