Have you heard someone say “the setting was like a character?” I remember the first time a teacher introduced the concept and my young, logical mind thought it was pretty stupid. A character is a character, a setting is a setting. Black and white, one or the other. But I was also pretty stupid as a youngin’, and as I read more, the more I seemed to gravitate toward novels that had a strong, if not overwhelming, sense of setting. It made everything else in the story – the plot, the characters, the conflict – feel real, no matter what genre. I especially love books set in the Midwest United States where I grew up. The characters feel familiar. Moon Over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool comes to mind. Set in rural Manifest, Kansas, the book carries with it familiar history of rural Kansas which informs the culture. And yet there is no town in existence named Manifest. That leads me to the first way you could add some magic into your real or realistic setting.

Have you heard someone say “the setting was like a character?” I remember the first time a teacher introduced the concept and my young, logical mind thought it was pretty stupid. A character is a character, a setting is a setting. Black and white, one or the other. But I was also pretty stupid as a youngin’, and as I read more, the more I seemed to gravitate toward novels that had a strong, if not overwhelming, sense of setting. It made everything else in the story – the plot, the characters, the conflict – feel real, no matter what genre. I especially love books set in the Midwest United States where I grew up. The characters feel familiar. Moon Over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool comes to mind. Set in rural Manifest, Kansas, the book carries with it familiar history of rural Kansas which informs the culture. And yet there is no town in existence named Manifest. That leads me to the first way you could add some magic into your real or realistic setting.

This first point is more of a confession. I adore the Sookie Stackhouse series by Charlaine Harris. Love it. I love Sookie and will defend every decision she makes in the series. Come at me, bros. Now that I’ve thrown my undying love out there, I can say one of the things I love the most in the series: Bon Temps (pronounced “Bauh Tauuuh” or some crazy phonetic spelling like that), the home town of Sookie Stackhouse. Bon Temps isn’t a real town in Louisiana, but it might as well be. The tone of the town, the people in it, the surrounding towns and communities, and the culture is dead-on small town Louisiana – everything from Sookie’s charm and manners to the people of the town knowing all the other characters’ business.

This first point is more of a confession. I adore the Sookie Stackhouse series by Charlaine Harris. Love it. I love Sookie and will defend every decision she makes in the series. Come at me, bros. Now that I’ve thrown my undying love out there, I can say one of the things I love the most in the series: Bon Temps (pronounced “Bauh Tauuuh” or some crazy phonetic spelling like that), the home town of Sookie Stackhouse. Bon Temps isn’t a real town in Louisiana, but it might as well be. The tone of the town, the people in it, the surrounding towns and communities, and the culture is dead-on small town Louisiana – everything from Sookie’s charm and manners to the people of the town knowing all the other characters’ business.

This isn’t an uncommon way for an author to give their setting culture and context, and for good reason. Setting can greatly change or enhance the flavor of your plot, much like salt can bring forth flavor in food.

Another way you can encapsulate the tone of a location is by describing it without naming the location specifically. Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West takes place in a war-torn country where Islam is a predominant religion. These are all the clues we are given as the reader. When the two main characters travel through doors (portals) to other countries, the cities they pass into are named: real cities, real countries. Written this way, Mohsin Hamid draws empathy from the reader, encouraging them to picture the main characters’ city as their own, or could be their city

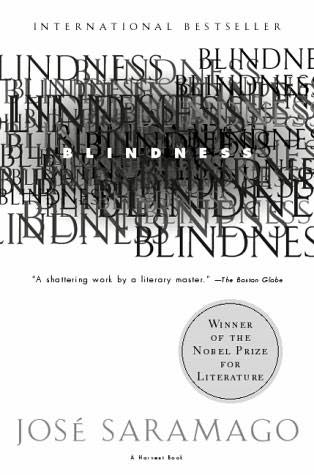

Another way you can encapsulate the tone of a location is by describing it without naming the location specifically. Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West takes place in a war-torn country where Islam is a predominant religion. These are all the clues we are given as the reader. When the two main characters travel through doors (portals) to other countries, the cities they pass into are named: real cities, real countries. Written this way, Mohsin Hamid draws empathy from the reader, encouraging them to picture the main characters’ city as their own, or could be their city  under similar political circumstances. Mohsin Hamid uses setting as theme in this case, as the plot circles around immigration and migration. In Blindness, José Saramago also offers up an unnamed setting, and yet it feels similar to every big city you’ve ever been to, adding to the creepy factor: this could happen anywhere.

under similar political circumstances. Mohsin Hamid uses setting as theme in this case, as the plot circles around immigration and migration. In Blindness, José Saramago also offers up an unnamed setting, and yet it feels similar to every big city you’ve ever been to, adding to the creepy factor: this could happen anywhere.

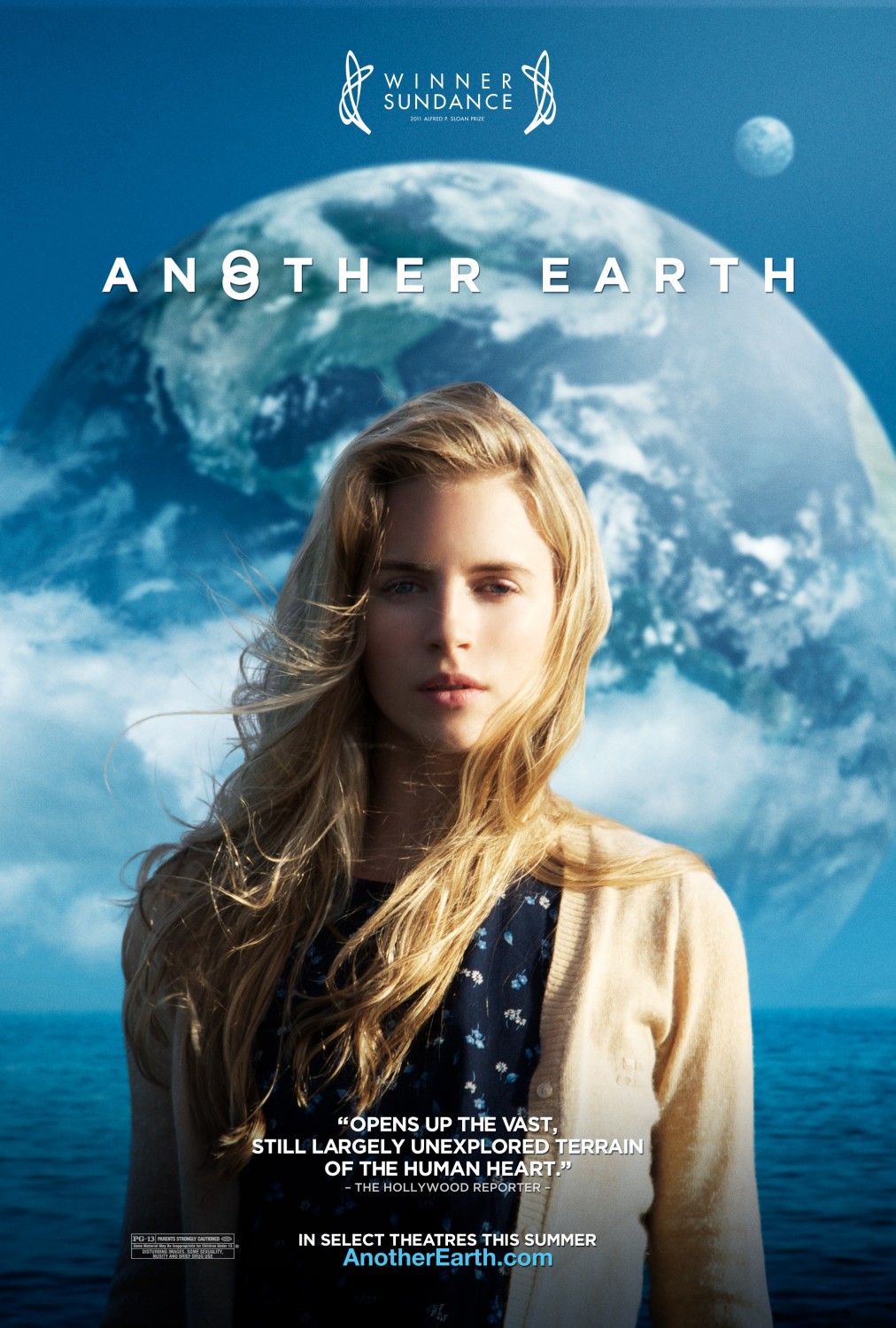

Sometimes, movies have the potential to introduce a unique setting that acts as a hook. Another Earth written and staring Brit Marling is a fantastic example of just that. The story is a tragic drama, a bleak indie film with the exception of the setting. While the story is set on Earth, early on in the story, an Earth 2 is discovered, and soon it’ll be orbiting near our own Earth. As it turns out, Earth 2 mirrors Earth not just topographically… It also mirrors its inhabitants – like an alternate universe. Everything plot-wise in the story is realistic – what we could unfortunately experience in every day life, like a car crash, a devastating death. The setting is Earth, and yet the viewer’s curiosity can’t help but be tickled with the presentation of an Earth 2, making the setting(s) a major player in the plot itself. This movie and its story wouldn’t at all have the same appeal without the setting. The setting is the hook.

Sometimes, movies have the potential to introduce a unique setting that acts as a hook. Another Earth written and staring Brit Marling is a fantastic example of just that. The story is a tragic drama, a bleak indie film with the exception of the setting. While the story is set on Earth, early on in the story, an Earth 2 is discovered, and soon it’ll be orbiting near our own Earth. As it turns out, Earth 2 mirrors Earth not just topographically… It also mirrors its inhabitants – like an alternate universe. Everything plot-wise in the story is realistic – what we could unfortunately experience in every day life, like a car crash, a devastating death. The setting is Earth, and yet the viewer’s curiosity can’t help but be tickled with the presentation of an Earth 2, making the setting(s) a major player in the plot itself. This movie and its story wouldn’t at all have the same appeal without the setting. The setting is the hook.

As a thought experiment, how could you make the setting in your current project into a character? The theme? The hook? It won’t take long to realize you have a lot to play with for storytelling when it comes to the setting. Take advantage of your setting -make it work in more ways for your book than just one.