A guest post by Sarah Bartsch.

A few weeks ago I was invited to write for this blog, told it’s the best-books-you’ve-never-heard-of theme, and one title immediately pops into my mind: Heroes Die by Matthew Woodring Stover, book one of the Acts of Caine. As always. Seriously, I’ve been recommending this book to people since 1998.

A few weeks ago I was invited to write for this blog, told it’s the best-books-you’ve-never-heard-of theme, and one title immediately pops into my mind: Heroes Die by Matthew Woodring Stover, book one of the Acts of Caine. As always. Seriously, I’ve been recommending this book to people since 1998.

I checked Librarything numbers to make sure it was still relatively “unknown”, and with only 491 people owning copies compared to 1169 of Runelords, 7,276 people having The Name of the Wind and (unsurprisingly) 76,945 copies of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s/Sorcerer’s Stone, I figured that was good enough.

So a couple weeks pass, life is life-y, and I get an email from Tor.com (as you do) all about their new article: “Reddit Fantasy Lists Under-Rated and Under-Read Fantasy.”

The Acts of Caine series is number one.

Great minds and all that, right? I’m glad even more people will go check out this great series, but it gets me wondering, and I go plug words into Google. Apparently the Acts of Caine is getting love all over the place. A lazy search revealed John Scalzi is a fan and did an interview with Stover in 2013 to coincide with the UK Orbit release. Scott Lynch gave Heroes Die a glowing review back in 2003, and that’s in addition to the Reddit survey I already mentioned and another lengthy recommendation for “The best damned fantasy you’ve never read” on the Penny Arcade forums.

So… my great idea for this post got stolen years before I even had it.

I’m okay with that.

Now a warning: This story isn’t for everyone. It’s violent, though not as gratuitous as it seems at first. It’s intense and may push some buttons or just irritate a reader in the wrong mood. It’s grimdark ten years before that term was coined. None of the characters are Good or Bad, but there are the people you’re clearly rooting for and then… there’s everybody else.

The story spans two worlds. On Arkhana, magic is real and warlords and kings fight for dominance, hiring women and men like Caine to do their dirty work. Caine is renowned as the best at what he does… while back on Earth, Caine’s adventures are experienced by an audience in the billions. Because Caine is actually superstar Hari Michaelson, who travels to Arkhana to kill for the sake of the profitable entertainment industry. Check out the links below for much better synopses if this grabs your attention at all.

But the most important thing I noticed about this book? A lot of people hate it. There are tons of bad reviews. Just scroll through the comments on the Penny Arcade post and you’ll notice negativity as often–if not more often–than praise. There’s even the occasional valid point I can’t argue away about the characterization or the style or whatever… Which just doesn’t matter because loving a book isn’t subject to logic. It’s about experience. Story. Visceral reaction.

As a writer, here’s my takeaway: Someone will always hate what I write. No matter what. I can follow all the rules (and practice) and attend workshops (and practice) and try to absorb greatness from my mentors (and practice), and even if scores of readers someday find my work brilliant, there will still be people who hate it. Worse, some will be completely unaffected either way, no matter what I do.

How… liberating.

So I’m going to swing for the fences with every story and hope, someday, something I write makes a fraction of the impact–both love and hate–as has the Acts of Caine.

If you want a proper recommendations, see below:

Scott Lynch’s review (yes, That Scott Lynch, the author of The Lies of Locke Lamora): http://www.rpg.net/reviews/archive/9/9825.phtml

John Scalzi interview with Stover: http://www.orbitbooks.net/2013/05/29/john-scalzi-interviews-matthew-stover-about-the-acts-of-caine/

Sarah Bartsch lives in Albuquerque, holds degrees in anthropology and history and has a passion for all genres of fiction. She earned a black belt in Shotokan karate and has fond memories of doing archaeology in Wales and Ireland, but she’s most happy at the moment making the final touches on an urban fantasy novel and celebrating her first short story sale. “Substituting Fluffy” will soon be published by Daily Science Fiction.

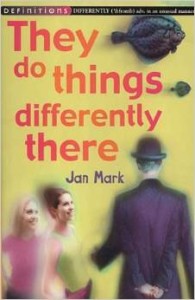

My family unearthed They Do Things Differently There (Jan Mark, 1994) at a library book sale when I was twelve years old. We had been consuming Jan Mark books for years and were very excited to discover a relatively new book of his shoved in amongst the clutter of salable discards. Every Jan Mark book I have read has endowed me with some new discovery of how to both play with the English language and appreciate life in general, but They Do Things Differently There was a crown jewel when I was young, and now, thirteen years later, I appreciate it all the more.

My family unearthed They Do Things Differently There (Jan Mark, 1994) at a library book sale when I was twelve years old. We had been consuming Jan Mark books for years and were very excited to discover a relatively new book of his shoved in amongst the clutter of salable discards. Every Jan Mark book I have read has endowed me with some new discovery of how to both play with the English language and appreciate life in general, but They Do Things Differently There was a crown jewel when I was young, and now, thirteen years later, I appreciate it all the more. Amy Groening is a publishing assistant at Word Alive Press. She is a passionate storyteller with experience in blogging, newspaper reportage, and creative writing. She holds an Honours degree in English Literature and is happy to be working in an industry where she can see other writers’ dreams come to life. She enjoys many creative pursuits, including sewing, sculpture, and painting, and spends an embarrassingly large amount of time at home taking photos of her cats committing random acts of feline crime.

Amy Groening is a publishing assistant at Word Alive Press. She is a passionate storyteller with experience in blogging, newspaper reportage, and creative writing. She holds an Honours degree in English Literature and is happy to be working in an industry where she can see other writers’ dreams come to life. She enjoys many creative pursuits, including sewing, sculpture, and painting, and spends an embarrassingly large amount of time at home taking photos of her cats committing random acts of feline crime.