When I was in my sophomore year, we all had to write a short story about whatever we wanted. Now, I’m not sure what I wrote; the assignment didn’t stick in my head because of what I did.

No, the assignment stuck in my head because of what my buddy Jacob did.

See, Jacob went for the most gruesome splatter-based horror story he could. It was the sort of story you’d expect from a tenth-grader, badly written and dripping in gore. At one point a series of people got taken out by a snowplow. Amongst all our friends, it was generally agreed that Jacob had produced a work of pure genius, to rival those of Poe himself. He got a C-.

See, Jacob went for the most gruesome splatter-based horror story he could. It was the sort of story you’d expect from a tenth-grader, badly written and dripping in gore. At one point a series of people got taken out by a snowplow. Amongst all our friends, it was generally agreed that Jacob had produced a work of pure genius, to rival those of Poe himself. He got a C-.

That story was so “awesome” to my tenth-grade self that I kept a copy of it. And while I was in college a couple of years later, I stumbled across it and re-read the stupid thing. I immediately concluded that “C-” had been generous. Grammar errors aside, the story structure had less cohesiveness than an average porn movie. Oh, the bodies were stacked up like cordwood, but that’s all the thing had going for it. That sanguine veneer covered exactly…nothing.

Now, none of this should come as a surprise to any readers here, save perhaps the fact that I’m talking about a writing assignment from High School at all. Of course it sucked-we were in the tenth grade.

But every time I sit down to try to write something dark, I remember that stupid story. I remember how fascinated I  was by it, and then how terrible it was. Those two extreme reactions are interesting and paradoxical enough that they form the core of my thinking about writing dark. And they’re the reason I rarely do it.

was by it, and then how terrible it was. Those two extreme reactions are interesting and paradoxical enough that they form the core of my thinking about writing dark. And they’re the reason I rarely do it.

Dark writing is often used as a way to cover up bad writing. And it should never, ever be.

There’s a lot of posts going on this month about pulpy fun. And that’s fine, so long as that’s the contract between the reader and the writer. Reader goes in expecting pulpy fun, reader gets pulpy fun, all is well in the world. But doing an intentionally pulpy story is one thing; being dark because it’s a substitute for being good is another.

Let’s take this to cinema for a second. You know why nobody liked Man of Steel? Because Grimdark Superman isn’t a thing. Zach Snyder took on the admittedly steep challenge of doing the Big Blue Boy Scout and completely muffed it. Superman’s a tough character to write specifically because you can’t simply go dark to get a serious edge to your story. You have to have a purely morally upright hero. It can be done–and done very, very well–but it pulls that crutch out from underneath you.

Let’s take this to cinema for a second. You know why nobody liked Man of Steel? Because Grimdark Superman isn’t a thing. Zach Snyder took on the admittedly steep challenge of doing the Big Blue Boy Scout and completely muffed it. Superman’s a tough character to write specifically because you can’t simply go dark to get a serious edge to your story. You have to have a purely morally upright hero. It can be done–and done very, very well–but it pulls that crutch out from underneath you.

Which should only serve to point out that there is a crutch here.

So, writing good dark fiction requires that one be aware of the fact that going dark can be a crutch. Keep it in your head at all times, because every time you add to the body count there should be a purpose to it. Every murder, every horrible monster; you need to look at the thing you’re trying to evoke in your reader. If it’s pulpy, campy fun, then fine; be up front that you’re going to have pulpy, campy fun. But if you want a really good, dark, horrific story then the first thing you have to do is stop thinking of it as a dark story and just think of it as a story.

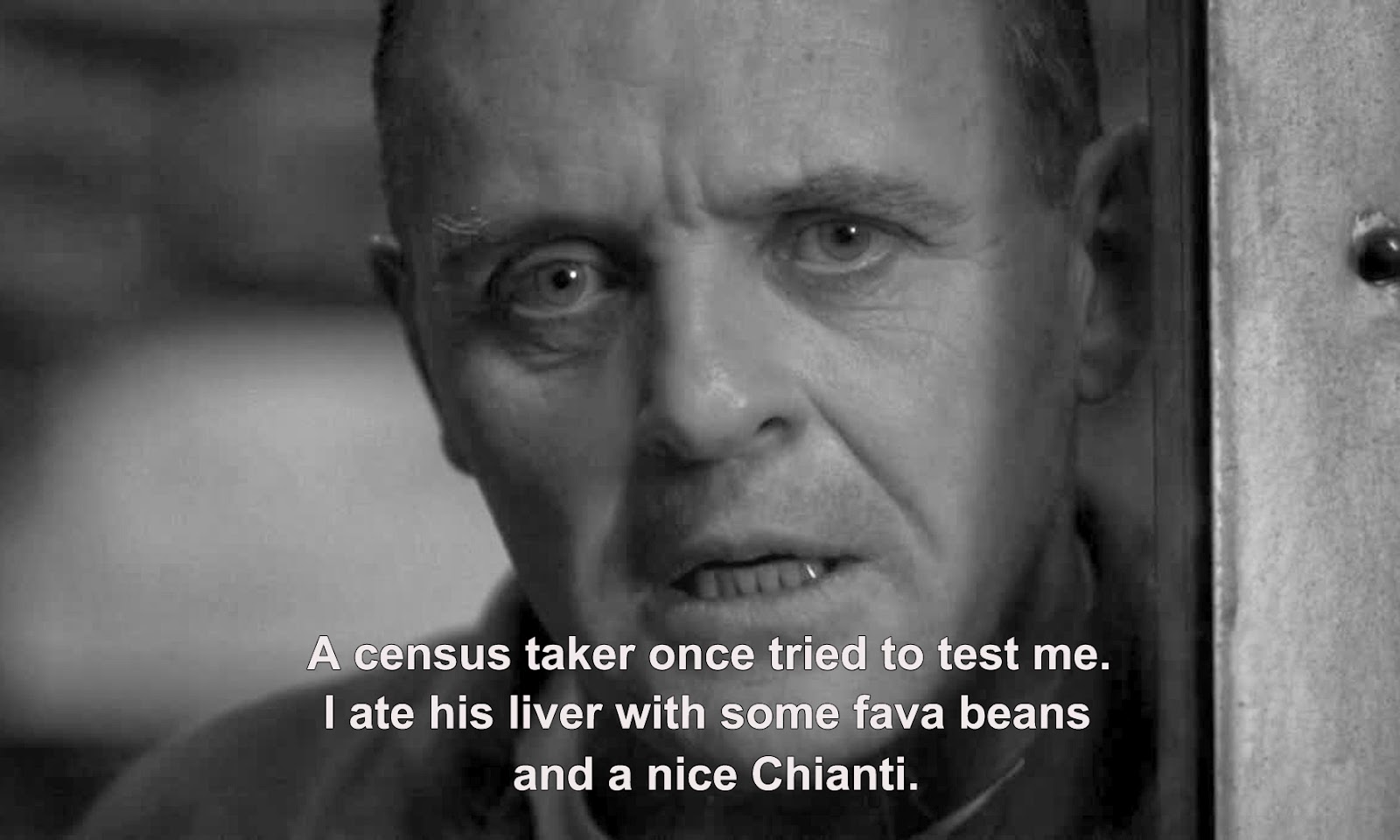

Your characters still need to be well-rounded. They still have to have real emotions, still have to think and be motivated realistically. If you have a villain–even one whose goal it is to go about gruesomely murdering people, then that villain needs to have reasons for what he or she is doing. Arguably one of the best horror villains written is Hannibal Lecter, and he’s not great because of his victims. He’s great because his murders stand out in stark contrast to his erudite intellectualism. He’s terrifying because we like him.

Your characters still need to be well-rounded. They still have to have real emotions, still have to think and be motivated realistically. If you have a villain–even one whose goal it is to go about gruesomely murdering people, then that villain needs to have reasons for what he or she is doing. Arguably one of the best horror villains written is Hannibal Lecter, and he’s not great because of his victims. He’s great because his murders stand out in stark contrast to his erudite intellectualism. He’s terrifying because we like him.

So, in short; the trick to writing good, dark fiction is to stop thinking of it as dark fiction. Write your characters. Give them a full life, and let the readers love them for who they are. Watching some random, faceless murdered commit atrocities is fun. Watching a character you love commit atrocities is terrifying.