Guest Post by Barbara Galler-Smith

I love history. I love perusing artifacts in museums. I love reading books and news bites of cool archaeological discoveries. You name it–if it’s old I am probably interested in it whether it be an old crumbling bit of textile, a 1500 year old castle, or ruins and petroglyphs of a long-gone people. It all has something to say. Most of all, I love trying to puzzle out in some Sherlock Holmesian manner just what it means in terms of people’s lives.

I love history. I love perusing artifacts in museums. I love reading books and news bites of cool archaeological discoveries. You name it–if it’s old I am probably interested in it whether it be an old crumbling bit of textile, a 1500 year old castle, or ruins and petroglyphs of a long-gone people. It all has something to say. Most of all, I love trying to puzzle out in some Sherlock Holmesian manner just what it means in terms of people’s lives.

So, when writing a novel, getting ready to write by doing research is half the fun. Some novels require a little research and others a lot. Historical novels usually require a lot.

Only two real “rules” apply to writing historical fiction of any kind, whether it be science fiction, fantasy, alternate history, mainstream, or romantic: Get the history right whenever possible, and use common sense when making up the rest.

Of course you don’t have to build a world–it’s already there just waiting for you to put your characters in it.

Getting the history right isn’t just checking a couple of links on Wikipedia–though that is a start. Good research is complicated and time-consuming. Visit large libraries, especially academic ones which have significant collections of books, research journals, and other support materials. Take advantage of interlibrary loans. Talk to fans of the era. Talk to experts. Experts, in fact, usually love to talk about their subjects, and they are often kind and forthcoming with little known and fascinating facts that almost never make it into the history books.

If you possibly can, go to the place you are writing about. If that’s not possible or practical, look at modern and historic maps. Your local college or university may have a map library that will fill in all those geographical holes for you. Also pick your friends’ brains–someone you know will have been right where you want to place your scene or chapter. Once you get the geography right, you may have to bend it a little to fit the story, but that’s all right–you’re writing a novel, not a factual academic treatise.

Look at old photographs or paintings from the period you are writing about. The style of dress of the people in medieval or renaissance paintings is the style of the times. Note the foods, how the houses are represented, even what the animals look like. Those paintings are a slice of life provided free and detailed by the artist.

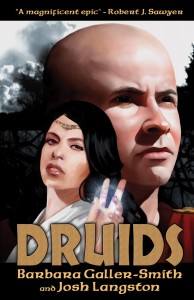

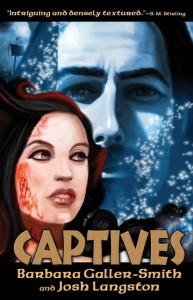

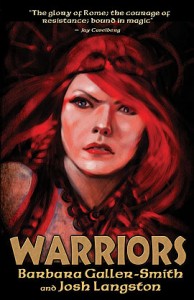

In our historical fantasy trilogy, The Druids Saga (Druids, Captives, Warriors), Josh Langston and I had extra  problems. We had three cultures to research, one well-documented, the others not. After weeks of investigation on what Romans were like: clothing and footwear, what they ate and drank, their social, economic, political structures, religion(s) and family life, and even their bathing habits–we had to do it all over again, this time for the Celts in non-Roman areas, and then compare and contract that with “civilized” Celts and Celt-Iberians who had been Romanized for over a hundred years.

problems. We had three cultures to research, one well-documented, the others not. After weeks of investigation on what Romans were like: clothing and footwear, what they ate and drank, their social, economic, political structures, religion(s) and family life, and even their bathing habits–we had to do it all over again, this time for the Celts in non-Roman areas, and then compare and contract that with “civilized” Celts and Celt-Iberians who had been Romanized for over a hundred years.

Then we had to make up the religion practised by the druids of Europe in the 1st century BC. Since we don’t really know exactly what the Gauls believed, we first examined what outsiders like Julius Caesar said about them and what modern archaeology tells us. Then, and most importantly, we looked at ancient practices still alive today, and the rites and rituals that go hand in hand with them. We made one big assumption–people haven’t changed much in 2000 years. Ancient ways remain in areas isolated from the modern world. We reasoned backwards–that if people do certain things now, then it’s likely they did similar things then.

We are still a superstitious and fearful lot. Spirits, ghosts, otherworldly creatures were real to many people back then, too. So, we looked at superstitions. We looked at symbols, signs, and even tattoos. We looked at coming of age ceremonies around the world noting that coming to womanhood and manhood are deeply important moments in a person’s life, and thus throughout history have had many rituals and rites associated with them.

All that research went into a big pot of information which we mined sometimes liberally but more often barely skimmed the surface of it to only add flavour to the narrative. We tried to encompass a broad spectrum of social behaviours, sometimes for colour but mostly to enhance the overall story and make it seem “true”. It all has to seem plausible.

You must do the same. Characters shouldn’t do what is not normal for real people to do.

You must do the same. Characters shouldn’t do what is not normal for real people to do.

If you decide to use real events and real people, there is some dispute over whether you can put words in historical figures’ mouths. While others have disagreed and called it disrespectful of the real person, I say go ahead. Just make sure you don’t change what they are known to have said, or make them speak in uncharacteristic ways.

In “Druids”, the first of our trilogy, we lucked out with Quintus Sertorius, a real Roman general. His character and life were outlined neatly for us by the Roman historian Plutarch. Sertorius’ life in Iberia provided a rough outline of how our heroine’s story would go set amidst the unrest at the beginning of the 1st C. BC.

One word of caution, our world view today has changed in ways nearly unimaginable to people who have not been exposed to concepts like civil rights, the sanctity of life, or environmental conservation. Today’s readers would be horrified at “real” history-its filth, superstition, disease, and cost in terms of human suffering. We have only to look at places in the world right now in which brutality is the meal of the day. Right now, enslavement or murder of one ethnic group is only a short airplane ride away–not a millennium or two ago. Fiction, especially genre fiction, set in brutal times or places may not be popular unless filtered through modern sensibilities and made more palatable. Verisimilitude is important. Sticking to the absolute truth in every horrid detail can be too much.

group is only a short airplane ride away–not a millennium or two ago. Fiction, especially genre fiction, set in brutal times or places may not be popular unless filtered through modern sensibilities and made more palatable. Verisimilitude is important. Sticking to the absolute truth in every horrid detail can be too much.

And one last word–we all suffer for our art, but please do not inflict your months of suffering research on unsuspecting readers. They’re just looking for a good story.

“Druids”, “Captives”, and “Warriors” (coming in august 2013) are published by EDGE Science Fiction and Fantasy Publishing. They are available in both paper and electronic versions. http://www.edgewebsite.com/

***

Barbara Galler-Smith lives in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. She’s an award winner author, a long-time member of Edmonton’s largest speculative fiction writers group, The Cult of Pain, and co-founder of a group designed for emerging speculative fiction writers called The Scruffies. She’s also a Fiction Editor for On Spec: The Canadian Magazine of the Fantastic. Along with US writer Josh Langston, she’s the author of The Druids Saga– an historical fantasy epic trilogy: Druids (2009), Captives (2011), Warriors (coming August 2013).

Yes, that is a TARDIS on my necklace.