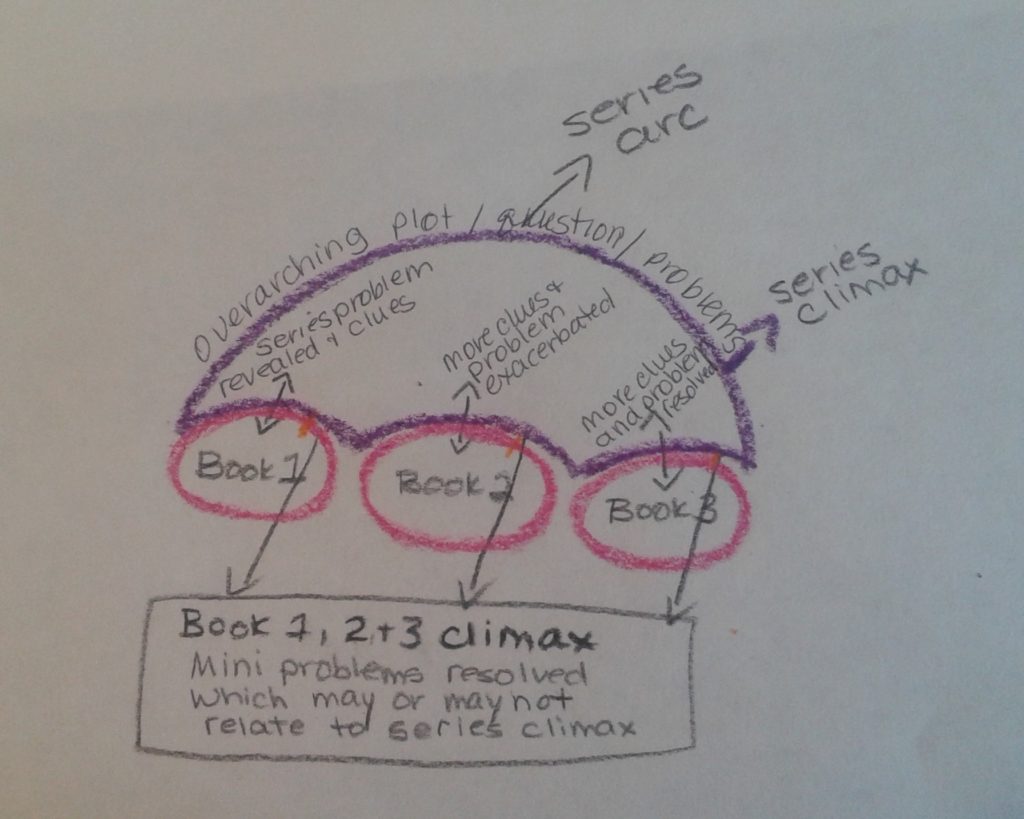

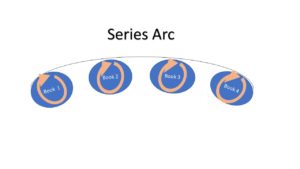

Writing a series is the process of telling multiple complete stories within the context of a greater story arc. Each book must be a complete tale in and of itself—with a standalone beginning, middle, and end all sparkling with vivid settings, rich characters, and intricate conflict. Each book sheds only enough light to reveal its portion of the grand design while steadily building tension, book to book, until all is revealed in the final installment. I speak to beginning writers all the time about crafting series. And, after leading off with the whole complete story deal above, I break out the Inception-esque logic of a book-within a book-within a book. Because, really, that’s what we’re writing. The story arc is our overall plot and each book can be seen as an act within the epic structure.

I speak to beginning writers all the time about crafting series. And, after leading off with the whole complete story deal above, I break out the Inception-esque logic of a book-within a book-within a book. Because, really, that’s what we’re writing. The story arc is our overall plot and each book can be seen as an act within the epic structure.

As a hardcore story plotter, or outliner, I need to flesh out the high-level arc enough to figure out where each book begins and ends along with the major concepts or plot points that need to be introduced or even resolved. But nothing is set in stone. The outline is more of a guideline as opposed to an absolute. During the writing process, the story and characters evolve. As they do, they affect the overall series arc, kinda like what Doc Brown harangued Marty McFly about—Be careful, Marty, changes in book one could alter the planned events in book four. Yes, they surely will. And that’s all cool and groovy with me because it means the story is deepening, the events stretching between books tightening, interweaving, becoming more connected to the main line.

Let’s see…talked about writing a complete story, shedding light, book within a book, each book like an act…what else? Ah, the hooks. Gotta keep the readers reading.

Just like when ending a chapter on a key revelation or decision point to keep the reader turning the pages, in the case of a series, we do the same. Only, it’s done on a grander scale. In the first book of a series, the writer introduces the conflicts that must be resolved in that book and sets the stage for the main series conflict. Of course, that can’t be resolved within the pages of a single book. If it could, we’d call that a stand-alone novel. The writer builds up the action and leaves the right open conflict threads to ensure the reader comes back for the next book. After the denouement, some riveting scene should occur that grabs the reader by the eyes and says, “OMG!”, whetting the reader’s appetite and leaving them wanting more.

Hooks in books in arcs.

Later,

Scott