A guest blog by Karen Traviss

On Friday we looked at ways to boost your storytelling by reworking your manuscript as a comic or a movie. This week, we move on to cauliflowers. Talking cauliflowers.

On Friday we looked at ways to boost your storytelling by reworking your manuscript as a comic or a movie. This week, we move on to cauliflowers. Talking cauliflowers.

I’m not immune to the ruts and barriers of writing even at this stage of my career. If you’ve followed my blog, you’ll know that the ability to spontaneously create sentient vegetables in a story, without apology and actually making it work, was a gift I envied, so I set about trying to acquire it. That was easier said than done. It wasn’t that I wanted to write fantasy per se, but that I watched how effortlessly manga and anime just went for it and made the utterly bonkers somehow seem perfectly reasonable.

For some of you, that’ll be how you write anyway, you lucky people. My natural habitat, though, is realism. That’s inevitable after careers in news journalism and related school-of-hard-knocks trades, and I’ve built a business on it. My readers like authenticity and I’m known for doing nose-bleeding amounts of research for the smallest detail or even for the background awareness that never makes it into the book. But the other side of rigorous realism is an inner censor: the disapproving mental voice that speaks up when it encounters a wild thought, and says, “Don’t be so bloody daft, that would never happen.”

We don’t need self-censorship. We already have too many external censors trying to tell fiction writers what they’re allowed to do and trying to prevent them from publishing what they don’t approve of. Censorship kills fiction: it makes for cookie-cutter stories built from tick-lists, and – perhaps worse – it removes an important safety valve for society. Fiction is where we can say the unsayable and make sense of what we see without enacting it in the real world. “What if?” Those are the most important words in fiction, and we don’t need a zampolit to give us permission to answer the question.

What some of us need, though, is a way to be equally defiant of the inner censor. For me, that meant risking falling out of love with anime and manga by analysing it. (Later I extended that to live action drama.) Usually, I have to choose between creating or consuming, because once I pick a side I can never switch back to the other again. But for some reason, this time I managed it. The Japanese – and the Koreans, I later found – take risks in fiction that we often shy away from in the West. Maybe I don’t see their taboos in the gaps because I don’t understand enough about their societies, but what I do see is a healthy sense of abandon to uncertainty. They really go for What If.

Genre lines seem not to exist. Random and incongruous is the order of the day, and they dip in and out of other cultures and mix nationalities without apology or apparent fear of “appropriation.” There are some consistent character archetypes, but nobody’s guaranteed to survive, win the love of their life, or even succeed in their quest. Happy ever after seems quite rare: but there’s plenty of suck it up and make the best of it. There’s often a massive reveal at the halfway point that changes everything you thought about the first half. And then there are the techniques like timeline loops and flashback reveals which can look odd to western writers who’ve been taught that you can’t hide things from the audience. (Okay, that’s still a big challenge if you write very tight third POV.) Somehow, the Japanese and Koreans make it all work magnificently.

So, having watched more Japanese and Korean TV and movies than I thought was physically possible, I felt I had a good grasp of what they were doing and how they did it. (And boy, did I enjoy it.) But recognising what they’re doing isn’t the same as being able to do it yourself. If I sat down and tried to force something wackier or more random onto the page, I just ended up doing what I always did: extrapolating, based on reality. That’s how I tell a story. I take the environment, work out the type of characters most likely to be there, shove them together, and let them run like a computer model.

Characters need to behave like real humans, but nothing else needs to be real. I still struggled with creating the unrealistic and the un-sensible. Eventually, the first glimmer of a turning point for me was when someone pointed out that I was often surreal and off the wall on Twitter, so why couldn’t I do it in a novel?

Because Twitter is a series of throwaways, the equivalent of a casual chat in the pub. That’s why.

My inner censor – even if I do apply common sense and a healthy wariness of getting sued – is off duty on Twitter. I don’t expect to have to do anything long-form or smart with a random observation, or have my career hinge on it, so I let it loose.

That realisation taught me that I have to be prepared to grab the loony thought and hold on to it, write it down, and ignore the voice that tells me to be sensible.

Over a lifetime I’d learned not to listen to the free association that was my brain doing what brains are made to do – trying to create patterns, even when those patterns are misleading and don’t exist.

I’m working on it. Some days I get a glimpse of what’s possible, but it’s still not how I think naturally, and maybe it never will be. But if I can detach enough from my own self to think like each character that I create, and believe what they believe and see what they see while I’m in their heads, then I should be able to detach a little further from the real world.

In the meantime, I’ll keep gorging on anime and sit glued to the latest Korean supernatural police procedural comedy thriller romance series (yes, all in the same show) and hope some that breath-taking ability to ignore risk rubs off on me. When my inner voice says, “You need a talking cauliflower there… ,” I shall be ready to listen.

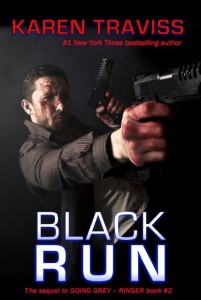

New York Times best-selling author Karen Traviss is a former journalist and has also spent way too much of her life around politicians and police. Going Grey, the first in her new techno-thriller series, and the sequel, Black Run, are available now.

Twitter: @karentraviss

I have a feeling you are a method writer in the same content of a method actor. I’m sure it’s exhausting. I can turn the switch off and climb back into the real world but I’m not sure you can. As I type this I’m not sure if I envy you or not. But it doesn’t matter what I think. Clearly you are in a spot all of us writer-wannabes envy.

Many of us follow our strengths and nothing else. Those who write sci-fi would never dream of creating a cute romantic /comedy complete with sunset and wine. My question is, why not? Every writer should challenge themselves the same way you did. Take a walk on a different path and see where it leads. It might surprise you.

Excellent article. Thank you.