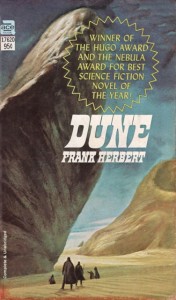

The year was 1967. I was standing in the store holding a copy of the first paperback edition of Frank Herbert’s Dune in my hand. It was huge. I don’t remember how many pages it was, but it was way larger than any single book I’d ever owned or read. The Lord of the Rings was the only single story I knew of that was larger. And it was priced at $0.95, which was an outlandish price for a paperback book at the time. Most paperbacks were either $0.40 or $.045, with $0.50 being the extreme. So Dune was running two to two-and-a-half times the price of a regular book. Of course, it was also about twice as long as a regular book. But I really had to talk myself into buying it. That was a lot of money for a sixteen year-old kid back then.

It helped that a cover quote from a name author compared Dune to The Lord of the Rings. I had discovered Tolkien the previous year, and was absolutely enraptured by Middle Earth, so anything that compared favorably to Tolkien’s masterwork certainly caught my attention. And that may have been the deciding element that ended up convincing me to buy it.

It helped that a cover quote from a name author compared Dune to The Lord of the Rings. I had discovered Tolkien the previous year, and was absolutely enraptured by Middle Earth, so anything that compared favorably to Tolkien’s masterwork certainly caught my attention. And that may have been the deciding element that ended up convincing me to buy it.

The quote author was pretty much on target. Dune is a masterpiece. It is absolutely the pinnacle of Frank Herbert’s career, having won both the Hugo and the Nebula awards for 1966, the only time he won either of those awards. None of his earlier works approach it in scope and awesome world building, and of his later works, only The Dosadi Experiment comes close to matching it.

At age sixteen, I had no clue that I would one day be a writer. Nonetheless, I learned an early lesson in writing from Dune, and that is the proper handling of a villain in a story.

Every story has to have a protagonist—the character the story is about. Just about every story will have an antagonist—the counterfoil that the protagonist plays off of or against. But the antagonist is not necessarily either ‘a’ or ‘the’ villain of the piece. In Dune, however, the roles of antagonist and villain are united in one character: Baron Vladimir Harkonnen.

The Baron is a real piece of work. Herbert draws him with bold lines as a man who seems to have no redeeming qualities. He seems to be purely evil, although naturally so. There is no supernatural element to the Baron as there is to Paul Atreides, the protagonist and hero of Dune. This, perhaps, makes the Baron even scarier than he would have been had he been portrayed as some sort of Satan-analog or anti-Kwisatz Haderach to counterbalance Paul.

Herbert made the Baron stick in my mind by understating him. The Baron is an absolute sadist, a pederast, and an incestophile, yet very little of that is shown “on screen” so to speak in the novel. The reader is given glimpses here and there of the raw evil lying beneath the surface of what is otherwise a very forceful, articulate, and urbane man. This is so effective in Herbert’s hands. I literally shivered when I first encountered the Baron in Dune. And even today, I can get a chill running up my spine if I reread those scenes, or think about them.

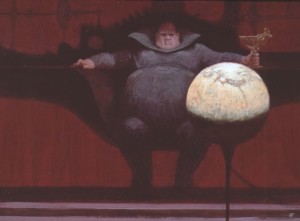

The other masterful approach Herbert took in limning the Baron for the readers is that his descriptions of the Baron’s physical nature were relatively vague and restrained. He seems to be a fairly big man, with a basso voice and hands and cheeks that are described as “fat”. He is described as being so large he needs “suspensor” units (small anti-gravity devices) to support his weight while he walks around. Yet there is little more given to the reader, so we are each allowed to visualize the Baron as we desire. Again, an understated style.

All of this combined in my mind to create an image of a very flawed yet very powerful man, a very sinister man. And it was all done without graphic or explicit presentations of violence, sex or debauchery. I was impressed by that character in 1967; I remain impressed with that character today, almost fifty years later. And the more I grow as a writer, the more impressed I am with the skill and craft and techniques by which Herbert evoked then and evokes now that most sinister of characters in my mind.

This was underlined in 1978 when the Dune calendar was published, which presented some of the illustrations the great John Schoenherr had done for the original magazine serializations in 1963-1965 of the early components of what became Dune. Frank Herbert praised Schoenherr’s illustrations as really capturing the essence and feel of the Dune universe. The following illustration was shown to a wider audience in the calendar, and I believe it shows the genius of Schoenherr, as that figure sitting in the shadows to me reeks of sinisterness.

But we can’t talk about Dune and not talk about the movie based on the book as realized by writer and director David Lynch, which was released in 1984. The movie has its fans, and it has its detractors. For myself, there were several things that I disagreed with the concepts of in the film (Bene Gesserit in pseudo-Victorian gowns, for example), but ultimately the film failed for me because of one significant element, and that was the presentation of Baron Harkonnen.

Even in 1984 I wasn’t naïve about the film-making process. I understood that textual works need to be adapted if they move to a different medium, and particularly in moving to the screen. So I was prepared to make allowances for that—even great allowances. But when I was sitting in the first run theater and the Baron came on the screen, I was totally blown out of the viewer’s trance, and I never really regained it.

Instead of the sinister figure of the novel, I was presented with a garish bumbler. Instead of the corpulent but smooth figure of the novel, I was presented with a not so large person covered by excrescences. Instead of the dominant controlling chess master who was coopting the Emperor, attempting an end run around the Bene Gesserit, and thinking and playing at least four moves ahead of Duke Leto, I was presented with a bumbling, almost slapstick figure who seemed to succeed in spite of himself and was himself being played by others. And instead of the smooth urbane deviant who controlled his passions and only expressed them when he was in control and when he felt it was safe, I was presented with a twitching idiot who would expose his lusts in public. (The whole heart plug scene fails on multiple levels.)

The nature and power of Baron Harkonnen is critical to the story that was told in the novel, yet Lynch gutted that character and turned him into a clown. And that, to me, is the major reason why the movie basically failed. I didn’t want it to fail. I wanted it to succeed. I wanted it to live up to the potential it contained. I wanted it to at least be a workmanlike and competent telling of the story. But by so radically transmogrifying the character of the primary antagonist who was also the primary villain, Lynch basically foredoomed the movie to failure as a story. (Transmogrify—thank you, Bill Watterson, for that lovely word.)

I know there are those who will disagree with my opinions and judgments here, but I call them as I see them. And the purpose here is really not to downgrade the film, but to expose the contrast between the two treatments of the same character. As writers, we can learn from both.

Baron Vladimir Harkonnen—one of the absolutely most sinister characters ever written. We can learn a lot from Frank Herbert on how to craft a villain.

Excuse me while I shiver.