It’s a dark and pulpy night…a perfect time for suspense–terror—gore–and…

…unicorns?

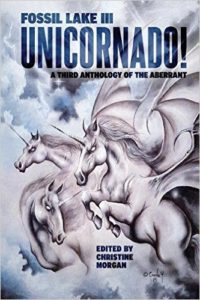

Fossil Lake III: Unicornado! is an Anthology of the Aberrant that mashes up horror tropes and weather-disaster movies with….glittery, sparkly unicorns.

Fossil Lake III: Unicornado! is an Anthology of the Aberrant that mashes up horror tropes and weather-disaster movies with….glittery, sparkly unicorns.

I’ve written about unicorns before–including in the two anthologies, One Horn To Rule Them All (A Purple Unicorn Anthology) and Game of Horns (A Red Unicorn Anthology), which raise funds for Superstars Writing Seminars’ Don Hodge Memorial Scholarship–but I’ve never written about unicorns quite like this.

One of the challenges I’ve had about being a writer who occasionally does horror stories is making sure my readers know what they’re getting from those stories. I’ve got a number of readers who are very excited about my science-fiction and fantasy work, but they’re upset by gore, or they can’t handle anything too scary. Meanwhile, I’ve got other readers who love the spooky stuff!

For those of you who write horror and self-publish, it’s a good idea to make sure your covers and blurbs reflect the content of your story, so people who don’t like the creepy stuff know what they’d be getting in your tale, and people who DO like the creepy stuff know that you’re someone they want to be reading!

I”m fortunate that my publisher wants to be absolutely sure that parents aren’t buying Unicornado! for their kiddies…unless their kiddies are Wednesday Addams!

The blurb makes it absolutely clear that these are not unicorn stories for the little ones.

So, how does one make unicorns scary?

In One Horn to Rule Them All, I wrote about a girl who strikes an alliance with a karkadann–a desert unicorn–and joins a group of unicorn warriors. Karkadanns are pretty scary–dangerous, aggressive, bloody, and hostile. If you’re not the karkadann’s ally, you’d be looking at a terrifying monster.

The mythological karkadann is thought to be based on the rhinoceros. When I was a child, I discovered that my grandma’s King James Bible mentioned unicorns, but my dad’s New English Version Bible translated that Hebrew word as “wild ox.” As a kid, I much preferred the idea that there had been what I knew of as a unicorn running wild in Biblical times.

So, a Biblical unicorn…of a very Old Testament variety. Mix in some of the storms and plagues that tormented Pharaoh when he refused to let Moses and his people go, and you have the makings of some very scary stuff.

My short story “Unicorn Prayers” is one of thirty-two tales of unicorn weirdness in Fossil Lake III: Unicornado! that range from the macabre to the bizarre.

Get your own unicorns here at

or in ebook format on

And beware of the things that sparkle in the dark.