Why does the hero usually benefit from a group of friends to support them, while the villain seems to go it alone, surrounded by toadies, henchmen, and often monstrous servants, but no real friends?

Why does the hero usually benefit from a group of friends to support them, while the villain seems to go it alone, surrounded by toadies, henchmen, and often monstrous servants, but no real friends?

A favorite example for me is David Eddings’ classic fantasy: The Mallorean. I loved this series when I read it as a teen, and one of my favorite aspects of it were the fantastic cast of characters. Their friendship, bantering, and personal quirks felt so real, and helped draw me into the story. Every one of them played an important role somewhere along the way, without which the hero could not have succeeded.

On the opposite end of the spectrum was a villain who casually killed just about everyone they knew as soon as their usefulness ended. The contrast was powerful and effective.

Another stellar example is the friendship between Frodo and Sam. Without Sam, Frodo was doomed. Antagonistic forces were always loners: Sauron, the Dark Lord; Saruman the White, who turned traitor and allied with Sauron, but couldn’t be considered a friend of the ultimate tyrant. Then there was the creature, Gollum. So alone he had developed schizophrenia to have someone to talk to. I was fascinated by Frodo’s attempt to befriend that broken, evil soul. In the process of allowing Frodo close, Gollum actually seemed capable of redemption, but when he rejected Frodo, his ultimate fall was guaranteed.

Another stellar example is the friendship between Frodo and Sam. Without Sam, Frodo was doomed. Antagonistic forces were always loners: Sauron, the Dark Lord; Saruman the White, who turned traitor and allied with Sauron, but couldn’t be considered a friend of the ultimate tyrant. Then there was the creature, Gollum. So alone he had developed schizophrenia to have someone to talk to. I was fascinated by Frodo’s attempt to befriend that broken, evil soul. In the process of allowing Frodo close, Gollum actually seemed capable of redemption, but when he rejected Frodo, his ultimate fall was guaranteed.

So why are friends necessary for the hero? I’ve come up with what I think are some compelling reasons:

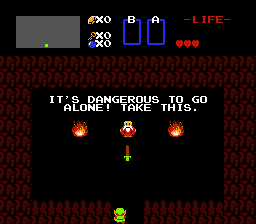

- The hero is usually the underdog in most stories. They’re caught up in crazy events that they usually would rather avoid, but cannot seem to escape. The enemy is usually far more powerful and dangerous. Without friends to help them develop and grow and become the hero the story needs, they’d never survive long enough to get a shot at victory.

- The hero must usually rise to fight some kind of evil, which means they represent the good. They might not be necessarily good of themselves, but they must represent good, or have ties to those they care about that are good. And those ties of love and friendship make them human, help readers relate, and encourage us to root for them.

- The hero is usually attempting to effect change. Real change cannot be done solo.

There’s a lot of great information about heroes and heroism out there. One resource I discovered is Matt Langdon of Heroism Science. He’s got an excellent post about heroism and the team heroes need to build in order to succeed. Check it out here: https://heroismscience.wordpress.com/2015/07/16/every-hero-needs-a-team/

Back to the villain. Why do they have so much trouble building friendships?

- If they’re truly evil, they simply can’t understand friendship, which is a form of love, placing it outside of the realm of understanding of a truly evil villain.

- True friendship requires acts of kindness and thoughtfulness, which is selfless and understanding. Most villains are proud and selfish, which again makes it nearly impossible for them to understand or embrace the necessary demands of friendship. Pride is by nature competitive, pitting the proud villain against anyone and everyone.

- However, if your villain is not one of those ultimate evil types, you might be able to craft one who gets it, at least at some level. Some of the most interesting villains are those who honestly think they’re right, who display kindness and honor, but who draw different conclusions about the world and how to fix it than the hero.

Think Magneto from X-Men. He’s ‘The Villain’ and he does terrible things. But through the story, he is portrayed as a man of deep thought and, at least initially, seems interested more in protecting mutants from abuses than causing them. He’s actually very good friends with Professor Xavier, even though they must face off time after time. The root of their differences is their different world view. That type of conflict is extremely fascinating.

Think Magneto from X-Men. He’s ‘The Villain’ and he does terrible things. But through the story, he is portrayed as a man of deep thought and, at least initially, seems interested more in protecting mutants from abuses than causing them. He’s actually very good friends with Professor Xavier, even though they must face off time after time. The root of their differences is their different world view. That type of conflict is extremely fascinating.

So build stories with great heroes and a stellar cast of supporting characters: the Mentor, the funny Sidekick, etc.

And when crafting your villains, consider making them human too, with real, complex motivations for what they do, with people they care about, and with real human emotions.

Those kind of villains are harder to hate, those stories are more complex, and often more difficult to write. But those are the stories that resonate the most powerfully. None of us will have to face the Dark Lord to settle the fate of the entire world, but we all have to face people who do mean or rotten things. Or maybe they’re just people who hold different political or religious views. It’s easy to see them as villains, but those people are human too, and although it makes it harder for us to hate them, they usually feel like they have good reason for what they do.

Deeply moving stories happen when the hero must stand against a friend. Find that story, and you’ve got a winner on your hands.

About the Author: Frank Morin

Frank Morin loves good stories in every form. When not writing or trying to keep up with his active family, he’s often found hiking, camping, Scuba diving, or enjoying other outdoor activities. For updates on upcoming releases of his popular Petralist YA fantasy novels, or his fast-paced Facetakers Urban Fantasy/Historical thrillers, check his website: www.frankmorin.org

Frank Morin loves good stories in every form. When not writing or trying to keep up with his active family, he’s often found hiking, camping, Scuba diving, or enjoying other outdoor activities. For updates on upcoming releases of his popular Petralist YA fantasy novels, or his fast-paced Facetakers Urban Fantasy/Historical thrillers, check his website: www.frankmorin.org

Consider as an example the action/adventure film John Wick. The introduction and inciting incident occur in the first fifteen minutes of the movie and the climax occurs at roughly one hour and fifteen minutes. Taken at a very high level, what happens during the hour between those two points? First, there is a period of milieu and character work to establish the character of John Wick and the rest of the world. Then there is a beating delivered by the big bad and the big bad’s first try/fail cycle to resolve the issue without violence. This is followed by a gun fight, a short period of world exploration, a gun fight, a brief pause for recovery, a fist fight, a briefer pause for a few wise cracks, a gun fight, a yet briefer pause in which John Wick sets some stuff on fire, and once again a gun fight that ends in a capture sequence. John then escapes captivity and dives straight into the climax of the movie. The tension is not allowed to slacken for a moment because John is near constantly either in danger and/or kicking some ass.

Consider as an example the action/adventure film John Wick. The introduction and inciting incident occur in the first fifteen minutes of the movie and the climax occurs at roughly one hour and fifteen minutes. Taken at a very high level, what happens during the hour between those two points? First, there is a period of milieu and character work to establish the character of John Wick and the rest of the world. Then there is a beating delivered by the big bad and the big bad’s first try/fail cycle to resolve the issue without violence. This is followed by a gun fight, a short period of world exploration, a gun fight, a brief pause for recovery, a fist fight, a briefer pause for a few wise cracks, a gun fight, a yet briefer pause in which John Wick sets some stuff on fire, and once again a gun fight that ends in a capture sequence. John then escapes captivity and dives straight into the climax of the movie. The tension is not allowed to slacken for a moment because John is near constantly either in danger and/or kicking some ass. I believe that the story of Arrival works as well as it does because everyone goes into a first contact story expecting an overt conflict between humanity and the aliens. However, twists this trope on its head, which is intriguing in and of itself. The main story is a mystery driven by the question, “What do the aliens want?” Along the way, we the audience are given pieces of the puzzle in such a way that they don’t all come together until the very end. This plotting structure latches onto our fundamental human curiosity and pulls us forward with the illusion of progress towards getting an ultimate answer.

I believe that the story of Arrival works as well as it does because everyone goes into a first contact story expecting an overt conflict between humanity and the aliens. However, twists this trope on its head, which is intriguing in and of itself. The main story is a mystery driven by the question, “What do the aliens want?” Along the way, we the audience are given pieces of the puzzle in such a way that they don’t all come together until the very end. This plotting structure latches onto our fundamental human curiosity and pulls us forward with the illusion of progress towards getting an ultimate answer. First is by introducing conflict internal to the relationship. By giving the romantic interests compelling personal conflicts and reservations, you allow them to stand in the way of their own happiness. It’s important to note that the reasons holding your characters apart need to be fundamental to their character, something substantial enough that it can withstand several try/fail cycles and significant enough that it poses a legitimate threat to the relationship. An example of this technique can be found in the early relationship between Eve Dallas and Roarke in Naked in Death by JD Robb. During her investigation of a sensitive homicide, Lieutenant Dallas meets Roarke and sparks fly. She feels conflicted because she can’t eliminate him as a suspect in her case, but also increasingly can’t deny her developing feelings for him. Her gut tells her that Roarke is innocent, but she can’t prove it. Robb draws us through the romantic arc by having Dallas’ blooming feelings clash with her sense of duty.

First is by introducing conflict internal to the relationship. By giving the romantic interests compelling personal conflicts and reservations, you allow them to stand in the way of their own happiness. It’s important to note that the reasons holding your characters apart need to be fundamental to their character, something substantial enough that it can withstand several try/fail cycles and significant enough that it poses a legitimate threat to the relationship. An example of this technique can be found in the early relationship between Eve Dallas and Roarke in Naked in Death by JD Robb. During her investigation of a sensitive homicide, Lieutenant Dallas meets Roarke and sparks fly. She feels conflicted because she can’t eliminate him as a suspect in her case, but also increasingly can’t deny her developing feelings for him. Her gut tells her that Roarke is innocent, but she can’t prove it. Robb draws us through the romantic arc by having Dallas’ blooming feelings clash with her sense of duty. The second option is to introduce some element of external conflict, where your romantic interests strive together to try to overcome a barrier from outside the relationship. Again whatever the threat is, it needs to be big enough to possibly end the relationship. Twenty three books later in Innocent in Death, Robb introduces one of Roarke’s old girlfriends into the storyline to give Eve an extra emotional complication on top of her homicide investigation. The ex-girlfriend’s presence causes friction between Eve and Roarke and in so doing threatens their, by then well established, relationship. In both cases, the emotional distance between the characters drives our readers forward; they want to make sure that Eve and Roarke end up together.

The second option is to introduce some element of external conflict, where your romantic interests strive together to try to overcome a barrier from outside the relationship. Again whatever the threat is, it needs to be big enough to possibly end the relationship. Twenty three books later in Innocent in Death, Robb introduces one of Roarke’s old girlfriends into the storyline to give Eve an extra emotional complication on top of her homicide investigation. The ex-girlfriend’s presence causes friction between Eve and Roarke and in so doing threatens their, by then well established, relationship. In both cases, the emotional distance between the characters drives our readers forward; they want to make sure that Eve and Roarke end up together.