I have found that there a few divides amongst writers more contentious than the arguments between discovery writers (pantsers) and outliners. I used to be firmly a member of the pantser camp. While I recognized that outlining had its benefits, I felt that planning with such excruciating detail would “ruin the fun” of creation. Plus, outlining was difficult and boring. The outline would only change as I got into the trenches and discovered something new and shiny, so what was the point? I had tried to outline a few times, I argued, and it hadn’t worked for me. It never would.

Fortunately, I had a few friends patient enough to take the time to convince me otherwise. Outlining isn’t a single, specific, regimented process, they argued, but rather a way of approaching a story deliberately. I would still create, discover the characters, the world, and the plot in the brainstorming section of the process. Then, the outline itself would be like writing an extremely condensed first draft. I would be able to edit it for major structural problems without the emotional baggage that came with hours and hours spent working on prose.

Once I had a coherent skeleton, I could write the first draft without worrying about writing my way into corners. My structural edits would already be done, and so I could focus my creative energies on producing powerful prose, vivid descriptions, and touching emotional moments. Not only would my first draft be better than what I had done before, it would also take less time to complete.

As for the “inefficiency” of prewriting, any time that I spent up front would be repaid twice over in the back end of the first draft. My manuscript would be leaner and free from most, if not all, structural problems. Additionally, outlines were guides, not shackles. Of course the outline would change as I wrote, but I would “discover deliberately” rather than wandering off into the weeds. I would be able to compare new ideas against a well thought out plot and be able to decide what was truly better for the story. Though it took a few years of conversations and cajoling, they eventually won me over.

Convinced, I decided that 2016 would be the year that I learned to outline. I struggled for a few months and grew disheartened. Outlining was proving to be as difficult, boring, and ineffective as I had feared it would be. I took my problems back to my writing group and we talked through numerous blocks. The issue, I eventually came to realize, was that I hadn’t learned the skills I would need to outline effectively. I knew how to work with character, with plot, with theme, and with milieu. I had all the pieces, but didn’t know how to put the puzzle together.

Again, I was lucky in that I wasn’t alone in my struggles. Of the three members in my group, two of us were discovery writers who were trying to make the transition. After some discussion, we decided to act as a group to resolve the problem. We enrolled in one of David Farland’s online classes, The Story Puzzle. Over the course of 16 weeks, the Story Doctor walked us through his process and theories, answered our questions via email and the biweekly conference calls, and provided valuable feedback on the writing assignments we submitted to him.

It was hard and frustrating at first, but eventually I found the joy that has always driven me to write. I was still discovering and creating, but by doing so deliberately I was finding more than I had expected. My story improved with each passing week and I began feeling the itch, the need to dive in and write prose. I resisted and kept working Dave’s process. By the end of the class, I had all the pieces that I needed and some good guidance on how to put them together into a functional outline. I was in no way ready to begin writing the first draft, but I knew how to get there.

Time passed as I continued to work on my outline. I built my world, wrote down scraps of description and dialog, and found ways to heighten my story and characters on every level. On the first day of each month, I surveyed my progress and decided if I was ready to start prose. Month after month, I judged that I was close, but not quite there. It wasn’t that I was stalling, like I had in the past when my project seemed intimidating. Rather, I had a task list that I needed to finish.

Then came the first day of another month. November first. NaNoWriMo had just begun. I looked over all of my prewriting and decided that, yes, I was ready. I dove into the prose and emerged thirty days later with my first ever NaNo victory. The story wasn’t done, in fact I had quite a ways yet to go. Rather, I had proved to myself that with a good outline to guide me, I could out-write my old pace by a fairly significant margin. Most importantly, I knew that I could do it again. And again. It was the sort of skill that I could develop into a career.

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release.

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release. However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing.

However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing. Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks.

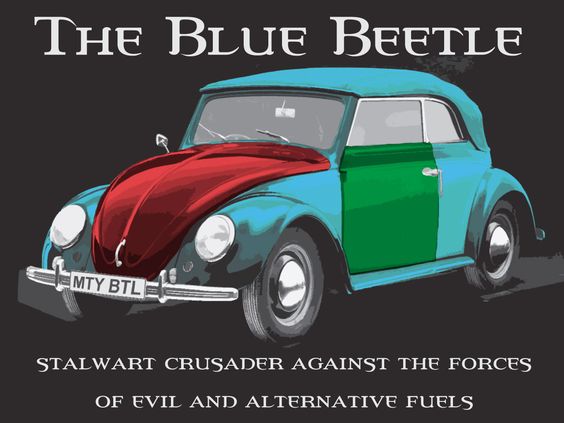

Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks. For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.

For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.