Pain is a part of life. Suffering is the human condition. It rains down on us and we wallow in it. It eats at our guts and we keep feeding it until there’s nothing left but a shell.

If there is anything that every single member of the human race holds in common, it is one thing.

Love.

All of us have loved. Most of us have lost. Lovers, children, parents, friends, pets. Betrayals, unravelings, deaths, or simply unrequited yearnings. All love comes together, and then it must, inevitably, come apart. Someone said that all love stories ultimately end in tragedy.

Rather than philosophize all the live-long day, I should point out that this is going somewhere.

Artists are uniquely suited among us to use that pain to illuminate the human condition. Music and poetry and prose comes along at just the right moment, lances that boil of loss that’s festering in one’s soul and lets healing begin.

On the way to the Odyssey Writing Workshop in 2009, I was driving through the forests of upstate New York toward New Hampshire, with a background noise of hurt emanating from how a woman I really loved was breaking my heart. And then some song I had picked up on a free Starbucks iTunes card cycled through my iPod for the first time and blasted a hole in my heart ten-miles wide, splattering bits of my soul all over the inside of the car. The song was “Sometime around Midnight” by Airborne Toxic Event, and it evoked a tidal wave of sad, sick, helpless desperation that I swam in for the next several hours. I listened to it over and over, memorizing every word. That song, in that moment, was about me.

So I arrived at Odyssey, started getting to know my amazing classmates and teacher, and settled in. The first week brought in the award-winning horror writer Jack Ketchum as a guest instructor. During his lecture, he said something I will never forget:

“In your writing, examine love always, and binding.”

And then Ketchum went on to explain that stories are almost always about love coming together, coming apart, or strengthening, renewing, reaffirming the bonds between characters. There are, of course, exceptions, but anytime you’re dealing with human beings in conflict, the crux of the story is almost always one of love’s multitude of forms. Even war stories are often the about the camaraderie among soldiers.

His lecture crystallized for me what I had been writing about for years. And throughout the rest of the workshop, I applied this newfound insight in every story I wrote.

And all that pain I had experienced in the car, I poured into the stories. They were raw, dripping with emotion. But they were real.

Today, in the midst of writing this, I was procrastinating over on Facebook, and another quote popped up on a friend’s feed:

“Great writing is not perfect; it’s real. It bleeds and leaves a trace.” – Jordan Rosenfeld, A Writer’s Guide to Persistence

The writing I produced in the midst of that pain back then is still some of my favorite, because it all came straight from the depths. It was far from perfect, but it certainly left a mark on me.

Writers of all stripes are uniquely suited to distill our pain into art. But what makes it “art,” rather than commonplace catharsis? Does anybody really want to read your therapy? Unlikely. It’s not the fact that you’ve had the courage (or neediness?) to put your pain on the page and show it to people. It needs to offer the reader something of value: a unique insight or perspective. What do you want the give the reader as they walk away?

Growth is a good place to start. People lose patience quickly with those who wallow in their pain for interminable periods and never learn from it, never get past it, or repeat the same mistakes over and over, and so will readers. What did you learn from your pain? Will your characters learn it too? What does your story have to say about love and binding? This discussion is leading us straight into the idea of “theme.”

You may not know what your story is about until you type THE END, but you should be able to look at it with an objective eye and identify its theme. The hard part here is being able to look past whatever emotions you mined to build the story to look at it objectively. All that raw emotion feels absolutely, 100% true and real to you, but not necessarily to the reader. You still must have the ability to lead them into it.

Just like nothing should get in the way of love, the writer should allow nothing to get in the way of writing about it, especially not worries about who will read it. You may have loved and lost, but maybe you can get a good story or two out of the experience.

About the Author: Travis Heermann

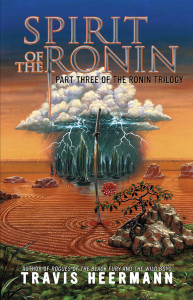

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Freelance writer, novelist, award-winning screenwriter, editor, poker player, poet, biker, roustabout, he is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop and the author of Death Wind, The Ronin Trilogy, The Wild Boys, and Rogues of the Black Fury, plus short fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines such as Perihelion SF, Fiction River, Historical Lovecraft, and Cemetery Dance’s Shivers VII. As a freelance writer, he has produced a metric ton of role-playing game work both in print and online, including content for the Firefly Roleplaying Game, Legend of Five Rings, d20 System, and EVE Online.

In August, 2015, he’s moving to New Zealand with a couple of lovely ladies and a burning desire to claim Hobbiton as his own.

You can find him on…