As a writer who gravitates to the dark and desolate and desperate, I often inject a syringe full of horror into my stories. “You got your horror in my fantasy!” “Oh, yeah? You got your fantasy in my horror!”

This month, I’m going to talk about a technique that the best horror writers and filmmakers use masterfully—leaving things off-screen.

So before this wild assertion spurs someone to argue with me, someone whose tastes prefer everything upfront and in one’s face, let me say that I enjoy strategic splatter.

The human mind—especially that of a hard-core reader—possesses prodigious powers of imagination. I was reminded of this when I was writing Sword of the Ronin, the second book of my historical fantasy trilogy. A number of beta readers expressed some difficulty at getting through a scene where the hero, who has been tortured and imprisoned for some time, has no choice but to witness the execution of a fellow prisoner. My wife read that scene and told me that it was one of the most excruciating things she has ever read. She was quite surprised when I pointed out to her that everything in that scene had happened off-screen, so she went back and looked at it again. None of what happens in that scene is visible. The protagonist only hears things and sees indirect evidence of what’s happening. Nevertheless, it is a scene that sticks with a great many readers.

H.P. Lovecraft said, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” His essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature” is where this quote appears, and is absolutely essential reading for anyone who wants to write scary stuff. He used this technique over and over again. So many of his most memorable beasties are terrifying because we can’t quite see them. In “The Dunwich Horror,” the creature is invisible. Ghosts scare us worst when we know they’re there, but we can’t see them. The monster in the shadows. The strange sounds in the night. The serial killer hiding among us. The guy next door keeping someone chained up in his basement.

You don’t want to use the clichéd, cheap jump from the cat exploding out the cupboard. You want the kind of tension that lets the audience keep squirming in their seats.

The bottom line is that we’re more afraid of what we can’t see than what we can. In the aftermath of a great horror book or movie, we remember the fear we felt during the experience, but don’t find the monster as scary anymore—because we’ve seen it.

Should you keep everything off-screen? You certainly can. It’s an artistic choice; some audiences prefer their horror a bit more sedate. But you don’t have to.

Allow me to point toward one of the most effective horror movies of recent years, The Descent, which tells the story of six women exploring an unmapped cave. This movie is an incredible mix of both on-screen and off-screen horror. First of all, it’s in a cave, so unless the flashlights are on, the screen is pitch black. On top of the incredibly claustrophobic environment (it was often a wonder to me how this was filmed), tension is built by half-glimpsed somethings at the edge of the light, or by strange sounds in pitch blackness. Throughout much of the film the horror is barely glimpsed, suggested, implied. But then at a certain point, the flood-gates open, the gloves come off, and we are drenched in blood, ichor, and violence. It was one of those movies that’s so effective at what it set out to do that I don’t think I want to see it again.

Like all tools—from paintbrushes to tack hammers to prepositional phrases—it’s the artist’s craft that decides when to use it to achieve the desired effect. Sometimes you need the splatter, the dripping fangs, all eight of the giant spider’s luminous eyes in hairy close-up. But those are often best used as part of the Big Reveal, the Climax, the Gruesome Finale. Sometimes, you need the shadows, the invisible threat, the last glimpse of a foot being dragged around a corner, the knife that wasn’t where you left it, the sound of something slithering through underbrush, to crank up the tension. Prime the audience with unrelenting tension so that the Big Reveal produces an audible gasp.

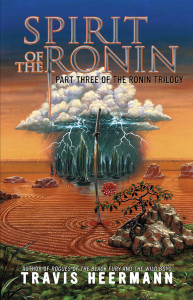

About the Author: Travis Heermann

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Freelance writer, novelist, award-winning screenwriter, editor, poker player, poet, biker, roustabout, he is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop and the author of Death Wind, The Ronin Trilogy, The Wild Boys, and Rogues of the Black Fury, plus short fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines such as Perihelion SF, Fiction River, Historical Lovecraft, and Cemetery Dance’s Shivers VII. As a freelance writer, he has produced a metric ton of role-playing game work both in print and online, including content for the Firefly Roleplaying Game, Legend of Five Rings, d20 System, and EVE Online.

He lives in New Zealand with a couple of lovely ladies and a burning desire to claim Hobbiton as his own.

You can find him on…