In my previous post, Know Your Story – 5 Simple Steps, I talked about creating a scene-by-scene outline from your first draft. The purpose of this exercise was to see the story’s structure. Structure included the shape of the plot itself and whether the scenes were structured in a balanced manner with a focus on exposition, action, dialogue, and reflection. I still recommend doing this to familiarize yourself with what you actually wrote as opposed to what you thought you wrote.

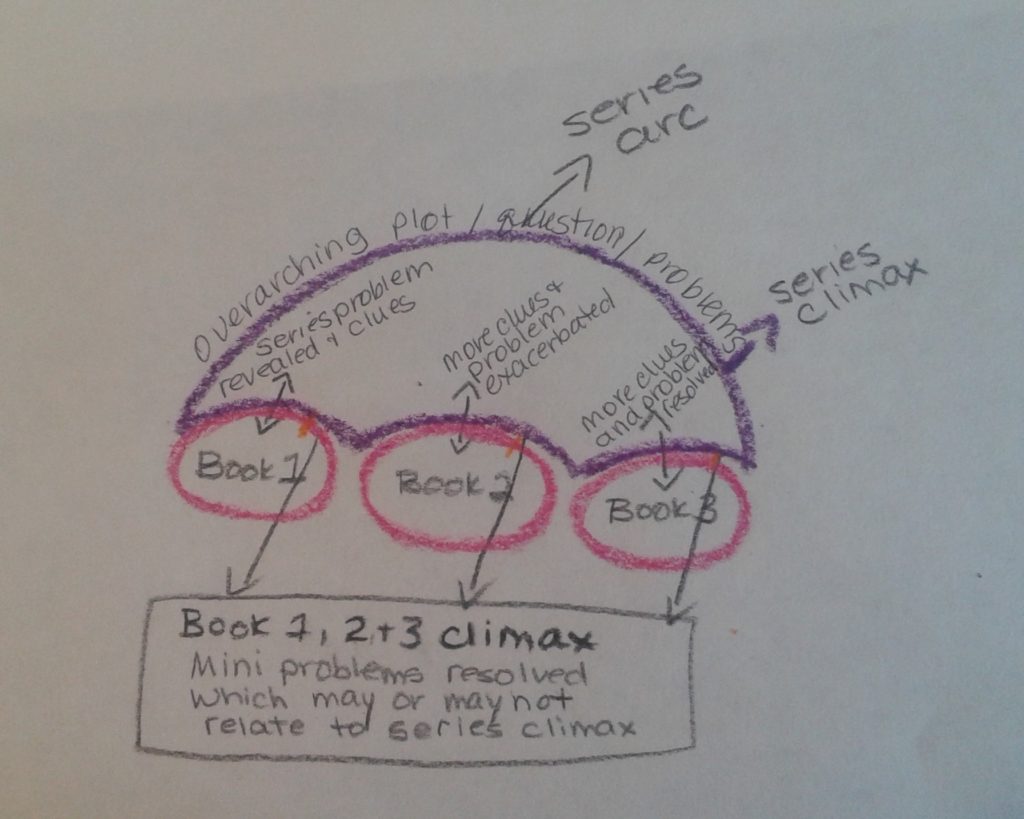

This is especially important if you’re writing a series because every book needs to build on the previous one. So, know what you wrote but don’t revise it just yet. PLOT your next book first before you begin revisions.

There is a theory out there not to write the next book in the series before the first one is accepted by a publisher. That’s silly, for so many reasons. Today, we have the option to self-publish. Even if a publisher accepts Book 1, that is not a guarantee that they’ll want Book 2. That depends on sales. But my main reasons for finishing a series, with or without a publisher are: a) I have momentum, a writing style and my characters and I understand each other well. There is no guarantee that I can pick up that vibe in the future; and b) the story is in my head, as is the character’s voice and a series is but one longer story to me. I have to write it; and c) I have publishing options and if a publisher publishes Book 1, and not the rest, I can build on whatever momentum I have and release the rest of the series.

But why plot the next novel before revising the finished one?

The future devils are in yesterday’s details!

I know an author who wrote the first book which was accepted by a publisher. In the throes of edits and final copy, the author set to work on the next book. Now, this author had ideas for the rest of the five book series and it was on that basis that the publisher bought the series. But, she didn’t have them plotted out. She didn’t need to because the concept and her writing were strong enough. The problems began when she created a more detailed outline for the next book. Details, information, actions, clues – all the things that could have foreshadowed and been used in the second book had not been included in the first book. She had written herself into corners or didn’t have the necessary tools for her characters in the second book. Creativity took on a new meaning and it was a challenge, albeit a doable one.

That is why I recommend outlining the next story before you revise the current story. Know the key plot points such as the beginning, the climax and the end. Jot down some ideas of how the protagonist and antagonist will arrive at the climax. What tools will they need? What characteristics will they require? Does the setting need to be described more richly so there aren’t any convenient contrivances? Are the subplots and relationships strong enough to sustain in the next story? Is this story’s world, and the characters rich enough to continue the melodramas and keep tension in the next novel?

When revising a story set in a series, the questions and story problems aren’t confined to the single novel. They affect the entire series and most importantly, the first book sets the stage, so make certain that the stage is set well, with enough detail, information and tools so that you don’t write yourself into a corner.

Always remember that the future devils are set in yesterday’s details!