A great plot and fantastic world building mean nothing without solid characters. Solid characters? Aren’t protagonists supposed to have weaknesses, flaws, desires which make them easier to relate to? And aren’t antagonists supposed to have soft spots to make them less stereotypical? True enough. But how do we determine those qualities?

Solid, well rounded characters, above all else, need value systems. What is the character’s core philosophy? What does he/she value above all else? What is most important? Family? Survival? Pursuit of knowledge? Loyalty? Money? Control? Love? Revenge? Adherence to rules? Fully realized characters have values which are challenged as they try to achieve their goals or live up to them. For example, an heiress, loyal to her father and his values which made him wealthy, searches for love and finds it in someone who hates everything her family stands for.

Value systems create opportunity for conflict and give characters depth. Once we’ve discovered those values, the plot comes alive as characters struggle to be true to themselves. For example, in The Hunger Games, despite all contestants valuing survival, they each value other things which motivate them: Katniss wants to save her sister and to avoid loving people but finds herself falling in love with Peeta who she’ll have to kill to win the competition; and Peeta wants to save Katniss but to do so, he must overcome his pacifist nature and kill others.

Value systems create opportunity for conflict and give characters depth. Once we’ve discovered those values, the plot comes alive as characters struggle to be true to themselves. For example, in The Hunger Games, despite all contestants valuing survival, they each value other things which motivate them: Katniss wants to save her sister and to avoid loving people but finds herself falling in love with Peeta who she’ll have to kill to win the competition; and Peeta wants to save Katniss but to do so, he must overcome his pacifist nature and kill others.

Ask – What three things does your character value the most?

The most important thing for X is: survival ….. adhering to the rules ….. scientific discovery …. family ….. avoiding love … finding love …. and so on.

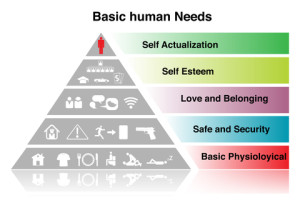

We can use Maslow’s Hierarchy to explore the range of values to determine which ones will create the most conflict for our character and our story. Maslow’s Hierarchy orders our human needs from the most basic to self-actualization. Remember, fulfilling our needs determines what our values are at any given point in our lives. That means we can be on level 1 while trying to achieve level 5 because conflicts are never tidy packages – they are individual to the person and even to the culture.

Maslow’s Hierarchy

Maslow’s Hierarchy

Level 1 – Survival: basics such as food, shelter, water, clothing, health – what the human body requires to function

Level 2 – Safety and security: personal (violence, natural disaster), financial, health and well being

Level 3 – Love/belonging: friendship, intimacy, family, this is our tribal nature of needing to belong in a group to enhance safety and survival needs

Level 4 – Esteem: being respected by others, needing status, recognition, fame, prestige, and attention. self-respect, mastery, independence and freedom. Respect = greater power

Level 5 – Self-actualization: concerns personal growth and fulfilment

Now use Maslow’s Hierarchy to understand your character’s values and to create conflict. Let’s start with Cindy. She’s a mom, a scientist and a peace activist.

Ask – What three things are most important for Cindy? What does she value? How does that fit into the hierarchy?1) winning the Pulitzer prize for peace by creating a Virtual web around the earth which neutralizes weapons (levels 4 and 5);

2) survival because nuclear proliferation threatens world safety (levels 1 and 2); and

3) her family (level 3).

Create your plot line by threatening all or some of the values or pitting them against one another:

Terrorists steal Cindy’s invention to use it to control all political powers on earth. Cindy must cooperate by agreeing to be their spokesperson and by activating the device in order to save her family. Will Cindy sacrifice her family to save the world? Will she die saving the world but be dishonoured as a traitor?

The higher levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy can be compromised by the lower basic needs or vice versa. Take a value and either go higher or lower on the chart to find a situation or value which can undo it. Ask what your character wants to gain and then ask how that can be undone or threatened by another value or what the effect of that will be.

Once you’ve determined your character’s values, putting them in emotional or physical conflicts which challenge those values makes for interesting reading. How your character responds to those situations creates wonderful opportunities for more action and reaction and moves the story along.

And, as an added bonus, focussing on values helps create the elusive pitch! Here are two quick pitches developed using Maslow’s Hierarchy and a character’s values.

Tom cannot remain the invisible technician aboard a space ship (level 4) when a computer virus compromises life support (levels 1 and 2) and he must overcome his insecurities (levels 4 and 5) to find the traitor before everyone dies.

Kim values family above all else (level 3) but his desire for wealth (level 2) puts him in a compromised position which threatens to bankrupt him and leave his family penniless (levels 1 and 2).

Using these examples create a story by exploring the protagonist’s values. Ask yourself: What is important to the character? What threatens his values? Now, create the supporting characters and determine what is important to each of them. Which of their values will conflict with the protagonist? What internal conflicts arise for each character?

By answering these questions, your plot comes alive through conflict, your characters rise beyond cardboard cut-outs and your readers, well, they’ll love you for it!

So, value your character by developing personal values which are threatened or clash with one another. Let those values drive the plot and watch your story come alive.

Happy writing!

Research sources:

psychology.about.com/od/theoriesofpersonality/…/hierarchyneeds.ht

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow’s_hierarchy_of_needs

www.businessballs.com Ҽ leadership/management

http://changingminds.org/explanations/needs/maslow.htm