A guest blog by Marie Bilodeau

Back in 2005, I wasn’t getting published. I had lots of stuff in the mail (SASEs, anyone?), but not many bites. I stumbled across storytelling, a performance art completely revolving around stories. I fell in love (with the idea of a captive audience, as most audiences are too polite to walk out). I took a class, started telling, and I’ve now had the chance to be a professional storyteller for 13 years, telling stories across Canada and the United Stated, in lovely settings like theatres, and shiny settings like under disco balls.

Back in 2005, I wasn’t getting published. I had lots of stuff in the mail (SASEs, anyone?), but not many bites. I stumbled across storytelling, a performance art completely revolving around stories. I fell in love (with the idea of a captive audience, as most audiences are too polite to walk out). I took a class, started telling, and I’ve now had the chance to be a professional storyteller for 13 years, telling stories across Canada and the United Stated, in lovely settings like theatres, and shiny settings like under disco balls.

In my early days, I thought that stories I’d tell would be great to published, and vice versa. Except for a few exceptions, I have been utterly and completely wrong. But this is so that each story can shine in its own medium, much like books don’t always translate well to movies.

The “why” is still a question that haunts me (haunts may be the wrong word here), but I have unearthed a few reasons:

The Thread

Like most storytellers, I don’t memorize my stories. I get up there and let the words flow (I do practice them, however. Sometimes.)

To make a story memorable, I typically memorize (more or less) three things:

- my first few sentences (so I can nicely set the stage)

- my last few sentences (to nail it)

- a few images / pieces of dialogue (to make it memorable / stand out)

Everything else has to flow for the audience to be able to follow (their brows furrowing is super distracting while you’re telling) and, to accomplish that, I also have to find the story thread. That’s the core of your story – the journey that everything hooks onto, from action to characters, so that it’s easy enough for the listener to sit back and enjoy the journey.

It doesn’t mean your stories are simple or that the thread is obvious! Think about some of the earliest oral storytelling examples: Epics, myths, legends, fairy tales… they all have similar beats. That’s the thread.

Also, and perhaps most importantly, if you know your story thread and you get lost while telling (a banging door, a screaming child, your feet hurt, you’re sweating under the spotlights), you can easily hop back in your story and improvise your way back because you know where to go. The teller must never break their own spell, after all.

The Audience

Your audience is there with you. You’re sharing a story, not just living it alone. You can throw in movement, song, a glance that highlights sarcasm. You’re living a story together, so you adapt as you go, to get your audience to feel or react in the best possible way. You can develop in-jokes, which you share only with your audience.

Because of the audience, the stories are never told the same. And because of you, the teller, they’re always a bit different.

You’re not just words. You’re a full package experience!

The Silences

These are similar to the breaks and white spaces in writing. But in telling, the hardest thing to get used to, and the most important, are the silences. It’s letting that empty space sit, so that your audience can digest something you’ve told them, make the connections and follow where you might be heading, sit with their emotions for a few moments. And you’re holding them by looking at your audience, sweeping over them and making eye contact, and they’re looking back, and every second feels like an eternity. You’re not there to hide, my friends. You’re there to deliver the story, silences and all.

Telling and writing may not be interchangeable (fully), but I know that they’ve helped each other get better. I’m better at story because of both of these art forms. Parsing a story differently is a great skill to develop, so even if the stage is not for you, definitely find a different medium to try out. Those skills will be handy in one way or another.

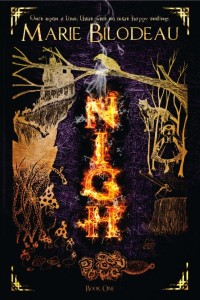

Marie Bilodeau is an award-winning science-fiction, fantasy and horror writer. Her latest book, Nigh, which she fondly describes as a “faerie-pocalypse,” is currently being serialized in bite-sized chunks, and is all about exploring tension through setting. Find out more about Marie at www.mariebilodeau.com.