Guest post by M.L. Humphrey

Writing a novel is hard. Few who set out to do so actually accomplish that goal.

But just when you think you’re in the clear–you’ve actually written and published a novel—you find out that writing a novel was the easy part. Because writing a series is about ten times harder than writing a standalone novel.

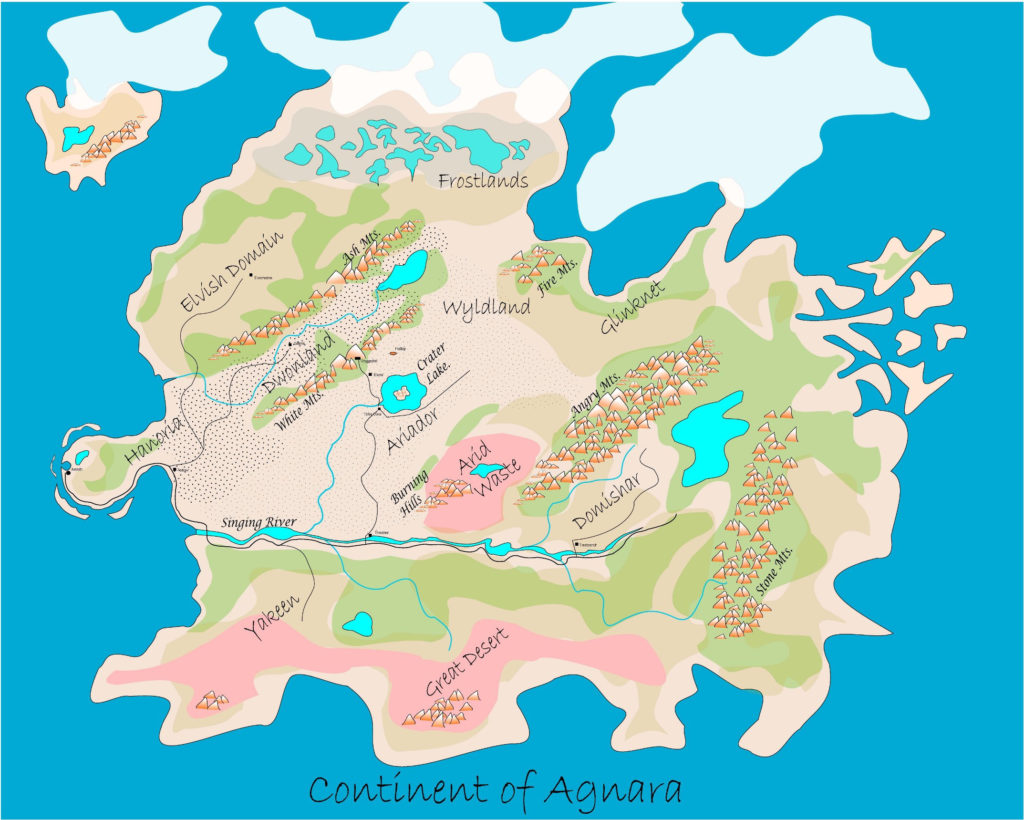

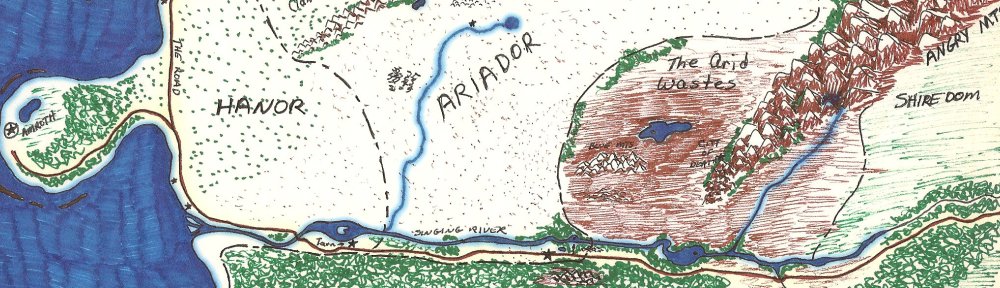

First, there’s the continuity issue. You told a story in book one and now that story has to continue in some way, shape, or form in book two. You can’t change your mind and decide to go in a completely new direction. You set down rules in book one and now you have to follow them.

Book two no longer belongs exclusively to you. Because the readers who are going to read book two are presumably the ones who enjoyed book one. And they have certain expectations. They want a continuation of the story they already started.

Of course, part of the challenge is, what story was that? Did they like your world-building? The playful banter between your two main characters? The way you explored that important scientific concept? The fact that your story included dragons?

I’m here to tell you, what you think you wrote is likely not what readers thought they read. I still remember a throwaway comment Peter Watts made on his blog about one of his novels. He thought he’d written a complex story involving cutting edge science. A large part of his audience for that book turned out to be teenage girls who thought he’d written a cool book about starfish. They were not pleased with book two.

So with book two you have to write a story that meets your readers’ expectations. Whereas book one was a clean slate and you could’ve gone in any direction, book two has a path it’s now on and needs to follow. (At least to some degree.)

There’s also the style issue. If book one was in first person, you should seriously consider writing book two in first person. If you wrote with short, clean sentences, you’ll want to keep doing so. If your first novel had long gorgeous phrasing that was like eating a ripe peach (you can tell I’m not that type of writer), you’ll want to continue with that. Because, again, readers have expectations based on book one that need to be met in book two and three and four and…Ugh. (This is why I write trilogies.)

Now, just when you were thinking this doesn’t sound so bad. It’s easy to continue that story you started in book one—that was the point after all—and that your voice is your voice is your voice, there’s one more obstacle to overcome.

Books two and three and four, etc. should also be different somehow. Your readers want more of the same, but not the same. If in book one your character climbed to the top of a mountain, found the sacred chalice, and saved the village, book two can’t have them climbing to the top of a mountain, finding the sacred sword, and saving the village.

(Yawn. Been there, done that.)

But have them wade through a swamp to find that sword and you’re all good.

So you have to mix it up. But not too much. Just enough to keep them guessing. While still giving them the same kind of experience you did with book one. Got it?

Easy, right?

Yeah, sure it is.

M.L. Humphrey is a self-published author who writes non-fiction, fantasy, and romance. She finished her first fantasy series, The Rider’s Revenge Trilogy (published under the name Alessandra Clarke) in 2017. You can find her talking about self-publishing (particularly AMS ads) and life in general at www.mlhumphrey.com.