By David Farland

By David Farland

In the past month, I’ve talked to dozens of new writers who are publishing their own books electronically. Everyone is doing it. In fact, I just put up six of my early novels along with several short stories. Within the next three weeks I hope to post the last of my novels and short stories, along with a couple of textbooks from my seminars (Write that Novel and Million Dollar Outlines).

Of course, that’s the problem. Everyone is self-publishing e-books. Bowker Identifier Services said that a million people bought ISBN’s last year, and another three million will be purchased this year. I spoke to one bestselling author recently who groused, “My neighbor came by last week and told me that he was a published author. He put up an e-book and sold seven copies. Then my paperboy told me that he was published, and he’s only fourteen! If anyone can publish, does it really mean anything anymore to be a published author?”

Well, it means something. It takes a lot of ambition and work even to self-publish, and as publishers keep cutting back on their own buying, it forces even known writers to move into that arena.

As an author, right now I have one foot in self-publishing, and one in the traditional markets. That’s an awkward position to be in.

With my latest novel, Nightingale, I’m going Indie. The standard contracts being offered by major publishers demand far too much from authors on electronic rights, and they really don’t give you anything in return. It’s a money grab.

So I had the best YA agents in New York offer to take the book to major publishers, and I told them “No.” I can’t in good conscience go that route.

So I decided to go indie. But there’s a rub. When you see an e-book from a self-published author, of course, you have to wonder if it’s any good. Is there a reason that the author couldn’t sell to mainstream publishers? Maybe, maybe not.

Sometimes publishers don’t take books that are perfectly good because the books don’t stand out. Sometimes the books have major flaws. Sometimes, though, the world’s just not ready for the author.

Tales are legendary of huge novels that had a hard time selling. Gone with the Wind, Lord of the Rings, Dune, and Jonathan Livingston Seagull are just a few of the classics that couldn’t get in print. More recently, The Help did the same before becoming a bestseller and a film. One can look back and find Nobel Prize Winners that couldn’t get published.

Years ago, I had one publisher ask me to look at their recent books and help decide which one to give the big “push” to. I surveyed about forty recent novels and picked a book called Harry Potter. The marketing department disagreed. The book was considered “too long” for its intended audience. I pointed out that it was written three or four grade levels too high, too, and said that they should push it anyway. The publisher took my advice, and the rest is history.

But there’s a lesson here. You as an author have to believe in yourself, and that’s what indie authors are demonstrating.

So I’m sure that great books will be coming from self-published authors. In fact, a year ago in April, I predicted that the first self-published author would become a millionaire within a year. It took about nine months before it happened.

But of course as book buyers, we have to worry that such books might have major flaws. We need to find a way of making sure that the quality is kept high. One way to do that is to join with other authors who vet the books. You can also hire editors like Joshua Essoe to suggest improvements, and so on.

With so many indie authors coming out, the markets will be flooded this year, and this leads to a new problem. Soon it will become harder and harder to stand out from the crowd. Readers looking for great content will realize that too often they’re paying to read from the slush piles, and they’ll probably start turning back to their favorite authors and to bestsellers in an effort to find works that they like.

In other words, they’ll realize that the gatekeepers-the editors and agents-served a purpose. Sure the gatekeepers weren’t perfect, but at least there was someone manning the guardhouse. The readers might even want to hire them back.

But New York publishing is a mess, and it won’t ever be the same. The big publishers are demanding so much of the profit from electronic rights that many of the best authors are leaving for good.

So readers will be looking for other ways to gauge novels. I think that writing awards, bestseller status, and positive reviews will gain more importance for buyers.

With this in mind, it seems to me that authors need a way to show that they stand out from the crowd.

We can’t return to the past. The overhead for paper publishing is tremendous-printing, storing and transporting the books is expensive. Most of the profit goes to the bookstores.

As the price for good electronic readers continues to drop, everyone will soon have them. School children will get them for school instead of books. Frequent readers will recognize that with the low prices of e-books, it will be far cheaper to buy novels electronically. Just as the whole country has switched to digital cameras, within five years nearly all of us will switch to e-readers.

So how will an author stand out in the electronic age? The answer is with “enhanced novels.” These are books that deliver text, but they can also deliver full-color illustrations, audio, film, games, and other components. In short, we’ll have editors who make the books into a major production.

We won’t spend huge amounts on printing, we’ll spend it on creating a great product.

With my partner Miles Romney, I’ve just completed my first enhanced novel as part of launching a new publishing company. It was an interesting and informative experience.

The novel is called Nightingale, and it tells the story of a young man named Bron Jones, who is abandoned at birth. Raised in foster care, he’s shuffled from home to home. At age 16, he’s kind of the ultimate loner, until he’s sent to a new foster home and meets Olivia, a marvelous teacher, who recognizes that Bron is something special, something that her people call a “Nightingale,” a creature that is not quite human.

Suddenly epic forces combine to claim Bron, and he must fight to keep from getting ripped away from the only home, family, and friends that he has ever known. In fact, he must risk his life to learn the answers to the mysteries of his birth: “What am I? Where did I come from? Who am I?”

So this is a young adult novel, and we decided to go with interior art. I didn’t want the art to be too much like something from a comic book, so we chose a more sophisticated style, similar to the art deco pieces that you might find in the New Yorker. Of course we looked at the work of dozens of artists before selecting our people. I didn’t want it to look like a novel that an amateur might put together.

We considered using a single artist, but we felt that that would take a long time, creating a bottleneck for production. It would also limit us to a single style, which might define the novel too much in the reader’s minds. So we opted to use several artists so that readers would be able to decide for themselves which ones came closest to their own personal visions.

We also wanted motion, and we considered some cool new styles of animation. I very much liked a minimalist approach, where only a single element in a still is animated. These are called “cinemagraphs,” and we could have made them with still photos, but instead opted to do it with illustrations. The idea here was that we found that if we put film at the beginning of a chapter, it competed for the reader’s attention, pulled them out of the book. So we made a game of having cinemagraphs in each chapter.

Now, it would have probably been easier and cheaper to film chapter headings, sort of mini-commercials for each chapter, in the long run, but we aren’t necessarily looking for the “easiest and cheapest” way to make a book. That’s been done for centuries. We wanted to “enhance” the novel, help bring it to life for readers who might find that visuals are helpful. We thought that hiring half a dozen fine artists would be fun.

We also wanted music to enhance the mood and tone of the novel, so we considered how to do that. Miles happened to know the head of the American Composer’s Guild, James Guymon, and so James came in to compose a 45-minute soundtrack. He called upon some smoking-hot professionals for help, including guitarists, lyricists, drummers, and so on. Since this is a story about a young man who dreams of becoming the world’s greatest guitarist, it inspired the musicians to put their best work out there. I had hoped to get some music in the style of guitar great Joe Satriani, and the album really blew me away. It’s much like the theme albums created by Pink Floyd or Joe Satriani himself. Portions of the songs are played as intros to chapters, but one can buy the album, too, from places like iTunes.

Of course, an enhanced novel can do more than just show animations and give us music, so we did put in some film clips, but we restricted them to author interviews, which we inserted along with notes and photographs on the making of the book. These are only visible if one reads the book in landscape mode.

Last of all we created the audiobook, hiring an actor to read it, inserting sound-effects and background music. So that the vision impaired, busy moms, and long-haul truckers can enjoy the book.

Then we’re also printing the novel in hardcover, since a lot of people still actually buy paper novels, and we lined up national distribution with an existing publisher so that we can get the books in stores.

The idea with our company is to push the novel in every possible format.

It has been a lot of work, and I’m feeling wiped. But our goal is to become an industry leader, to pioneer the next wave in publishing. We don’t have unlimited multi-million dollar budgets, but that will come.

I know for certain that I could have sold this novel to a major publisher. I did have the top agency for the genre ask to take it out to the big houses. But I didn’t want to go that route. This book is special to me, and I wanted to showcase it.

So the novel is out now, and Miles did one last cool thing. The enhanced book was made for the iPad, though you will also be able to read it on just about any other pad or smartphone. But Miles had his people create a web app so that you can enjoy the book on your computer-read a few chapters, take it for a test drive, or simply buy it for reading online. You’re free to go check out the results at www.nightingalenovel.com. If you like it, remember to “Like” us on Facebook. Better yet, re-post our site info and tell your friends on Facebook.

Oh, and while you’re there, check out our short-story contest, where you can win $1000.

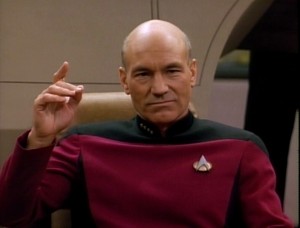

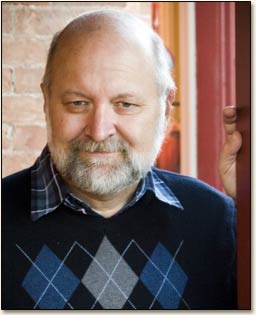

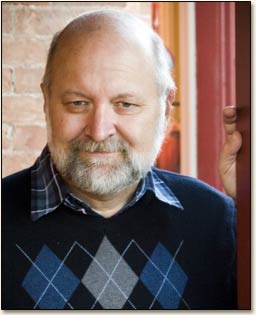

Guest Writer Bio:

David Farland is an award-winning, New York Times bestselling author who has penned nearly fifty science fiction and fantasy novels for both adults and children. Along the way, he has also worked as the head judge for one of the world’s largest writing contests, as a creative writing instructor, as a videogame designer, as a screenwriter, and as a movie producer. You can find out more about him at his homepage at

http://www.davidfarland.net/.

By David Farland

By David Farland