An interview with author Jayne Barnard.

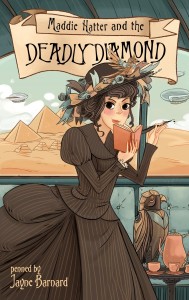

Mystery writer and steampunk aficionado Jayne Barnard has written a smashing novella, MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND. The novella is fun and the world Jayne created is fascinating. Steampunk, if done right, feels like a period in history that we should have studied in school and where Jayne’s book is compulsory reading. For all these reasons, I had to interview Jayne.

Mystery writer and steampunk aficionado Jayne Barnard has written a smashing novella, MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND. The novella is fun and the world Jayne created is fascinating. Steampunk, if done right, feels like a period in history that we should have studied in school and where Jayne’s book is compulsory reading. For all these reasons, I had to interview Jayne.

We had so much to talk about however, that you’ll have to read the second part of the interview Dueling Parasols and Creating a Steampunk World, Jayne Barnard Tells All to learn why Jayne chose to pay homage to certain personalities, her steampunk fashion choices and about the sport of dueling parasols!

Being a Steamlord’s daughter must be oppressive because Maddie vies to stay out from under her father’s thumb. Her class status, though, gives her insights (and privileges) into the upper echelons of society which are delightful for the reader to see. What is it like to be a Steamlord’s daughter and why does Maddie wish herself to be so independent from it?

Maddie Hatter comes from one of the three earliest Steamlord families. Her great-grandfather invented a mechanism that allowed steam power to be used for a much wider variety of purposes than before. The family’s wealth is almost beyond counting; they live in a vast subterranean mansion, have servants for every possible task, and travel everywhere by private luxury airships. They’re the 1% of their era. But a peerage only four generations old is barely a blip to English aristocrats who can trace their lineage back to the Norman Conquest. The Steamlords want to improve their family trees by marrying into the Old Nobility, which is lineage-rich but often cash-poor.

That’s the pressure Maddie is escaping: to be handed off, along with a well-padded dowry, to some family even more restrictive than hers, and spend the rest of her life taking tea with her mother-in-law and bear children for some inbred aristocratic fop, all so her father can fulfill his inherited duty to advance the family’s social and political power. Maddie is a girl of spirit and independence, not about to tamely submit to having her whole life decided for her before she’s twenty.

It must have been hard for Maddie to leave home and learn to fend for herself but she can’t seem to make a complete break. Why is making a complete break hard for her?

Since fleeing her home, Maddie has had to learn to do things for herself that a girl of any lesser family would have learned at a much younger age: to dress herself, care for her own clothing, organize her own meals, and most especially to earn her own living. She managed for two years on her own, and now has made a sort of peace with her family, becoming a female variant of the remittance man. That adventurous breed historically – often reckless younger sons who embarrassed their family once too often – was sent abroad to live or die as they chose. Their families paid an allowance on condition they stayed away and kept the family name clear of scandal. As a woman, Maddie’s not paid well for her work. Her father’s allowance is all that she will be able to save toward someday buying a home, or for her eventual retirement. A little older and wiser now since venturing on her own, Maddie knows that she can’t realistically make a complete break until she is earning enough to fund her future life as well as her current adventures.

The gadgets: mechanical birdie, airships, coffee service – you’ve got a wonderful smattering of them which makes Maddie’s world very interesting. Her little mechanical bird, Tweetle-D, who so delightfully inks things he’s seen, who is Maddie’s spy and is so helpful to her job. What inspired you to create him, and why him instead of a human helper?

Steampunk runs on clockworks, the brassier the better. To create the gadgets in Maddie’s world, I needed to only look around at daily activities and think: if this world were operating by a combination of steam power and clockwork controls, how could – for example – making and serving tea be done? As for the mechanical bird Tweetle-D, or TD as he is more often called, he is small, mostly quiet, but quite a personality for all that. He serves as a confidant for Maddie while she is cut off from family (by her own choosing) and from friends (by her assignment in Egypt). While he can’t fly far on his own, he travels well by airship, train, river-steamship or even by camel if necessary, and with far less fuss and bother than a living animal companion would require. And he’s got mad skills in note-taking and picture-taking, both essentials for a young lady trying to make her way as an investigative journalist.

Maddie is precocious, very liberated and besides needing to keep her true identity secret, she’s fighting for a place in a man’s world of crime reporting. She’s strong, as are all the female characters in this world. Is this historically accurate?

This story is historically accurate in the sense that young women ‘of good family’ who grew up in the late Victorian era were finally breaking out of the wife-governess-nun straitjacket, entering the workforce as shopgirls, office workers, nurses, authors, mathematicians, professors, and yes, as reporters. Maddie’s story is partly inspired by the barrier-breaking American journalist, Nellie Bly, who in the 1880s tackled a great many stories outside her early purview of fashion and society gossip. She not only went undercover (as Maddie also did) in pursuit of stories – most notably as an inmate in an insane asylum – but she set the record for getting around the world in under 80 days. As an inspiration for a young lady journalist, she’d be hard to beat. But then, this story is also inspired by the true story of a British colonial officer who stole a fabulous diamond ‘eye’ from a temple in India.

Less historically accurate but equally inspiring were the stories written by Jules Verne or H.G. Wells, the Indiana Jones and Young Indiana Jones movies, and my wonderfully imaginative friends in the Steampunk community in Calgary.

It’s as if the women have found a way to do what’s important and be themselves despite the obstacles. Is this story a social commentary?

This is first and foremost an entertaining story of one young woman taking on the world.

As for social commentary, women in the West have continuously struggled to take and keep control of our own financial security despite the political, social, religious, and economic barriers thrown up in front of us, our mothers, our grandmothers, and our daughters. More than a century after Maddie and Nellie Bly, women have still not achieved the grail of equal pay for equal work, except in unionized workplaces. Despite women outperforming men academically in sciences and mathematics, there are still glass ceilings and male-dominated industries and professions. The internet shames women relentlessly for sexual conduct (including for reporting rape or assault) as much as any Victorian society matron would, and threatens women’s lives for speaking up in some perceived male bastion (Gamergate, anyone?). Just recently, the female premier of Alberta was threatened with assassination by men who disagreed with her politics.

I didn’t set out to write a feminist fiction but the element most fantastical of all in Maddie Hatter and the Deadly Diamond may be that the women all found a way to do what’s important and be themselves despite the obstacles, and nobody threatened – or tried – to kill them for it.

That concludes this part of our interview. If you’d like to read MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND and see what other people have said about it, you can find it at Amazon and Tyche Books, and there are reviews on Goodreads.

Be sure to check out Dueling Parasols and Creating a Steampunk World, Jayne Barnard Tells All – you don’t want to miss out on dueling parasols!

Jayne Barnard is a founding member of Madame Saffron’s Parasol Dueling League for Steampunk Ladies and a longtime crime writer. Her fiction and non-fiction has appeared in numerous anthologies and magazines. Awards for short fiction range from the 1990 Saskatchewan Writers Guild Award for PRINCESS ALEX AND THE DRAGON DEAL to the 2011 Bony Pete for EACH CANADIAN SON. She’s been shortlisted for both the Unhanged Arthur in Canada and the Debut Dagger in the UK. You can visit her at her

blog or on

Facebook.

Let’s just get the argument out of the way first. Kristin, you’ve already said Outlining Your Novel was fantastic for me to have. How is Structuring Your Novel any different? Doesn’t she just repackage the material covered in Outlining Your Novel in this book?

Let’s just get the argument out of the way first. Kristin, you’ve already said Outlining Your Novel was fantastic for me to have. How is Structuring Your Novel any different? Doesn’t she just repackage the material covered in Outlining Your Novel in this book? K.M. Weiland breaks up her book into two sections: the macros of story structure and the micros of story structure. The macros include: the hook, the beginning, the first act, the first plot point, the second and third acts, the climax, the resolution, and the ending. Some of these macros are similar, but Weiland breaks down their differences, what percentage into your book they should occur, and why each are important. She also outlines some common mistakes and pitfalls, how to avoid them, and how to fix them.

K.M. Weiland breaks up her book into two sections: the macros of story structure and the micros of story structure. The macros include: the hook, the beginning, the first act, the first plot point, the second and third acts, the climax, the resolution, and the ending. Some of these macros are similar, but Weiland breaks down their differences, what percentage into your book they should occur, and why each are important. She also outlines some common mistakes and pitfalls, how to avoid them, and how to fix them.