I think the worst feedback I ever got from a beta reader was “It was good.”

I think the worst feedback I ever got from a beta reader was “It was good.”

“What would you change, if you could change anything about the story?” I asked, fishing for more details.

“I wouldn’t change anything.”

“So my manuscript is perfect in every way?” I was skeptical. It would be great to have written a flawless draft, but also not very likely. “Really?”

My beta reader looked uncomfortable. “I don’t want to hurt your feelings with critique.”

There it was. I had to coax my beta reader that I wanted critique. I needed honesty about aspects of the story that weren’t working. I had hoped to analyze reader responses and decide if I needed to revise my techniques. Did my readers feel that I was confusing them by being too oblique, or talking down to them with heavy-handed foreshadowing? I wouldn’t get the feedback I needed if all I received was a vote of confidence.

I didn’t need a cheerleader to be emotionally supportive. I needed someone who would dissect my work and tell me honestly about things that weren’t working.

#

At the other extreme, writers of my acquaintance have had beta readers whose feedback is a bundle of unhelpful negativity. “Your plot sucks.” “I hate your main character.” “This setting is stupid.”

#

The beta reader you want is someone in the middle. You need beta readers who are willing to be up front and honest if they find problems with your story, but you also want beta readers who will express that feedback in a helpful and constructive manner.

“This plot sucks” is no more useful than “This plot is good.” Why does it suck? And there are certainly ways to phrase such feedback that are just as effective and far more civil than “this plot sucks.” “This plot hinges on a series of implausible coincidences?” “This plot gets bogged down in the middle, making it likely that readers will lose interest?” “This plot has a major hole – the main character has a cell phone he uses to order a pizza, but never thinks to use it to call for help?”

If a beta reader can clearly identify problems, the writer will then be able to choose how (or if) to address those problems.

If? Well, it’s possible the beta reader misunderstood the story. If that’s the case, rather than fixing a nonexistent plot hole, the writer might want to concentrate on making the events read more clearly.

“My main character’s cell phone fell out of his pocket after he ordered that pizza. But my beta readers all missed that. Perhaps my language was too subtle. Maybe instead of writing that “he felt a strange lightness in his pocket,” I should be more explicit. I’ll have him reach into his pocket instead and discover that his phone is gone. Then it’ll be clear to my readers what happened.”

Come back tomorrow for some tips on how to find those beta readers in the middle!

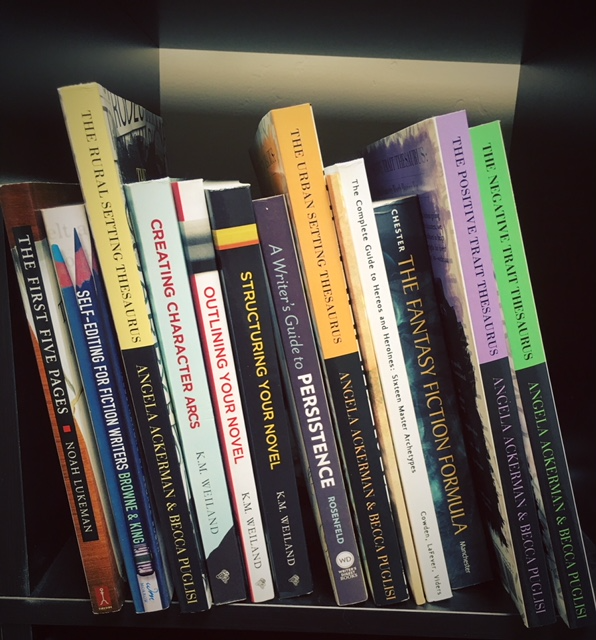

Any good writing website or book worth its salt will tell you your next step is to revise the sucker. Yes, you must do this step. Yes, everyone else hates it, too. Some books or fellow writer humans will advise you to put the book down for a set period of time to let it “rest,” like a good yeast bread needs a good rise. Unfortunately for your book, it doesn’t keep getting better in that resting period like bread does. No, no. It’s still the piece of crap you left a few weeks ago. So instead of the story rising like bread, think of it this way: YOU’RE doing the rising. You walked away for a few weeks and grew wise enough to rise above the piece of crap you made in order to come to a place where you can look past your subjective love of the story and objectively say, “Ah yes, indeed, this is a piece of crap.”

Any good writing website or book worth its salt will tell you your next step is to revise the sucker. Yes, you must do this step. Yes, everyone else hates it, too. Some books or fellow writer humans will advise you to put the book down for a set period of time to let it “rest,” like a good yeast bread needs a good rise. Unfortunately for your book, it doesn’t keep getting better in that resting period like bread does. No, no. It’s still the piece of crap you left a few weeks ago. So instead of the story rising like bread, think of it this way: YOU’RE doing the rising. You walked away for a few weeks and grew wise enough to rise above the piece of crap you made in order to come to a place where you can look past your subjective love of the story and objectively say, “Ah yes, indeed, this is a piece of crap.”