Nothing makes a professional author chuckle like listening to potential writers deciding to get into the field. Far too many think it’s easy to write a book and then have publishing companies dump shipping containers of hundred dollar bills on your front lawn. While this is a theoretical possibility (E.L. James comes to mind), it’s not probable.

I thought I would pick a few common lies that wanna-be writers tell themselves. Enjoy!

Writers Make Lots of Money

If only this was true. The best advice any professional author can give you is “don’t quit your day job.” You will need the income stability for yourself and your family, plus you may need the healthcare benefits if your day job provides them. Other benefits include life insurance and retirement contributions.

If only this was true. The best advice any professional author can give you is “don’t quit your day job.” You will need the income stability for yourself and your family, plus you may need the healthcare benefits if your day job provides them. Other benefits include life insurance and retirement contributions.

A study in the United Kingdom showed the average income for a professional author was £12,500, or $15,400 per year. That’s up from $11,000 per year, but only because the British Pound has declined in relation to the U.S. Dollar ever since Brexit was approved. Either way, fifteen grand and change will not go much further than paying some of your bills.

Is it possible to get rich writing? Yes, but again, not likely. You may have similar luck playing the Powerball and Megamillions lottery twice a week.

My recommendation? If you feel the call to write, then write and publish. Don’t go in with the idea you’ll get rich. If it happens, congratulations. Maybe you want to switch over and write full time, now that you no longer have to worry about money. You can work towards that goal, and you can change the odds with improving your craft and continuing to publish.

Writers are Experts in Language and Grammar

I have yet to meet one, although I would hedge and say that J.R.R. Tolkien is probably one of the closest. Every author I know makes a ton of mistakes when writing. After all, that’s why editors were invented. Editors typically have a better grasp of the mechanics of language…or at least the great ones do. The editors will comb through your work and fix all of those comma splices and split infinitives, vacuum out the extra commas, and polish the correct letters when you use to, too, or two.

I have yet to meet one, although I would hedge and say that J.R.R. Tolkien is probably one of the closest. Every author I know makes a ton of mistakes when writing. After all, that’s why editors were invented. Editors typically have a better grasp of the mechanics of language…or at least the great ones do. The editors will comb through your work and fix all of those comma splices and split infinitives, vacuum out the extra commas, and polish the correct letters when you use to, too, or two.

The purpose of an author is to tell a fascinating story in a logical methodology. Things have to happen and destinies and lives should be changed. Focus on that while doing your best to learn more about using proper grammar. At the very least, your editor will appreciate the effort.

You Can Never Become an Author

This is the saddest lie one can tell themselves. You’re basically convincing yourself not to even try, although you want to. You might be the magic lottery winner (and not Shirley Jackson’s version) if you start to curate your thoughts and words onto a page.

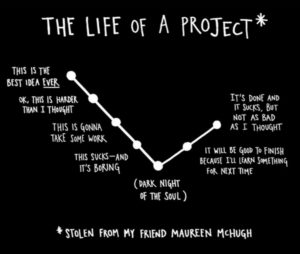

Is it hard work? Hell yes, it certainly is! It takes a lot of writing, editing, re-writing, and re-re-writing to put out a decent story. You can’t wait for your muse to inspire you if you’re gunning for the professional author title. Writers write, and that means there is no time for things like “writer’s block”. Can you imagine not selling coffee at your day job because you’re not feeling your coffee muse? Writing is just that, a job. That means you need to learn to be productive. There are a lot of suggestions and recommendations on how to do this on The Fictorians. In fact, this October and November, there will be a NaNoWriMo theme that stresses productivity.

Is it hard work? Hell yes, it certainly is! It takes a lot of writing, editing, re-writing, and re-re-writing to put out a decent story. You can’t wait for your muse to inspire you if you’re gunning for the professional author title. Writers write, and that means there is no time for things like “writer’s block”. Can you imagine not selling coffee at your day job because you’re not feeling your coffee muse? Writing is just that, a job. That means you need to learn to be productive. There are a lot of suggestions and recommendations on how to do this on The Fictorians. In fact, this October and November, there will be a NaNoWriMo theme that stresses productivity.

In the end, focus on the craft. Notch out some time from your busy schedule, even if it’s only an hour, and use that time to write just as if you were going to your day job. Produce new words. Edit old ones. Learn new skills. Read new books outside of your favorite genre. Improve yourself instead of lying to yourself. One has to realize that most of the time we’re our own worst critic.

I believe in you, for one. Now go earn some more fans.