“One writes such a story not out of the leaves of trees still to be observed, nor by means of botany and soil-science; but it grows like a seed in the dark out of the leaf-mould of the mind: out of all that has been seen or thought or read, that has long ago been forgotten, descending into the deeps. No doubt there is much selection, as with a gardener: what one throws on one’s personal compost-heap; and my mould is evidently made largely of linguistic matter.” – J. R. R. Tolkien, on the creation of The Lord of the Rings

Where do your stories come from? Writers are often asked that question.

The short answer: they come from leaf-mold, like Tolkien says.

As Tolkien was a philologist, the leaf-mold of his life was largely the study of languages and their relation to history, so it’s no wonder why Middle Earth’s races and history are so meticulously constructed.

Let’s deconstruct the above quote and expand its scope.

“One writes … not out of the leaves of trees still to be observed…”

We’ve got to have some experiences, don’t we? Experiences that elicit deep passions, loves in all their forms from crushes to parental bonds, betrayals, butt-kickings, travels, successes, and failures. We need to know what things feel like. We need to have laughed, wept, exulted, raged, and trembled in sufficient quantity to infuse our art with truth. The hearsay of truth, the derivation of truth, and sight of truth on a distant mountaintop is not sufficient fodder for art. Our truth must come from our own experience, not someone else’s.

…[N]or by means of botany and soil-science…”

Conscious thought is death to the creative process. It has uses, but only after the story exists in some form. The study of stories will not create a good story–although it could be argued that feeding your compost with the masterworks of your field forms a rich foundation. In the composition process, we must get the hell out of our own way. The subconscious wants to tell the story, but we fill up our awareness with fears and over-thinking, like scum on top of a crystal clear pond.

A quote from one of my favorite Japanese writer/philosophers, Takuan Soho, a 17th-century Zen monk, sheds more light here.

“One may explain water, but the mouth will not become wet. One may expound fully on the nature of fire, but the mouth will not become hot.”

Knowledge of fire and water comes with experience of fire and water, not from talking about fire and water.

We can’t write stories by talking about stories, deconstructing stories, or applying criticism to stories.

“[B]ut it grows like a seed in the dark out of the leaf-mould of mind: out of all that has been seen or thought or read, that has long ago been forgotten, descending into the deeps.”

Good writing comes not out of our immediate experiences today, the things that are immediate in our minds, our current traumas, but from experiences that we have assimilated.

Writing about an ongoing heartbreak might have value in catharsis, but the immediacy of the raw emotions can blind us to deficiencies in the work. Time lends perspective.

But here’s the thing. Our subconscious remembers. Those experiences will always be there. Water in the well. Leaf-mold covering the floor of our subconscious forest.

“No doubt there is much selection, as with a gardener: what one throws on one’s personal compost-heap….”

And there you have the crux of it. What do you throw into your leaf-mold? Some of it, you get to choose. Education? Choice of field? Work experience? Travel? Military service? Relationships? Long-distance bike trips? Having children? An obsession with cosplay, motorcycles, firearms, history, pro wrestling, forensics, or another wild passion?

Use the good stuff, the kind of stuff that will be nourishing at the next stage. Don’t put Snickers wrappers and pop cans in your leaf-mold. Fill it with the remnants of glorious feasts and breathtaking bouquets.

Things I’ve consciously added to my own leaf-mold include travel to places such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Bali, Cuba, and Costa Rica, plus living internationally first in Japan for three years and now New Zealand, activities such as martial arts training, bicycle trips, motorcycle trips, stock car racing, a Bachelors Degree in Engineering, a Masters Degree in English, learning some chords blues riffs on guitar so I can make a little music when it suits me, studying Texas Hold’em, seeking out music that fuels the creative stardrive, and cultivating awesome friends who feed my writer soul.

We throw the best stuff into that compost pile, rake it around, and boy does it get rich!

And also full of worms, and beetles, and spiders, and grubs. Those things just get in there, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

Some of it, you don’t get to choose.

- An abusive, controlling parent/significant other.

- A loved one’s struggle with chronic or deadly illness.

- Finances gone horribly awry.

- Natural disasters.

- The experiences of war.

- Accumulated injustices, prejudice, and betrayals.

Unwilling additions to my compost are things like divorce, poverty, long-ago injuries resulting now in chronic pain, illness in the family, a lifelong struggle with weight, the deaths of loved ones, unrequited love, and a host of trials, failures, successes, and incidents long since receded into the past.

One of the cool things about being a writer is that we get to right a few wrongs, even if only in our own heads and the heads of our readers.

We can get the girl/boy.

We can tar and feather that politician and ride him out of town on a rail.

We can save our parent from cancer.

We can rewrite history.

We can give just desserts.

We can create our own worlds where justice prevails. And those choices we make in our stories bubble forth from our experiences, our desires, our sense of right and wrong, our pain from those who have wronged us.

If people don’t wish us to write about them, they should behave.

Here’s the thing again: it’s all leaf-mould.

Everything we experience, whether accidentally or on purpose, leaves its tracks on our hearts. When those tracks are deep enough, ubiquitous enough, we must write about them. Consciously cultivating a rich leaf-mold will reward the writer with a great life on the front end and better writing on the back end, the kind of writing that makes readers weep and thrill and ponder and exult. The world needs more of that kind of writing.

So you owe it to the rest of us. Live an awesome life, and then imbue your art with that awesomeness.

About the Author: Travis Heermann

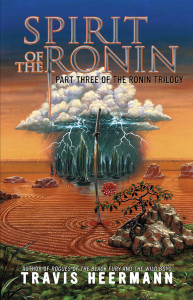

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Freelance writer, novelist, award-winning screenwriter, editor, poker player, poet, biker, roustabout, he is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop and the author of Death Wind (co-authored with Jim Pinto), The Ronin Trilogy, The Wild Boys, and Rogues of the Black Fury, plus short fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines such as Perihelion SF, Fiction River, Historical Lovecraft, and Cemetery Dance’s Shivers VII. As a freelance writer, he has produced a metric ton of role-playing game work both in print and online, including content for the Firefly Roleplaying Game, Legend of Five Rings, d20 System, and EVE Online.

He lives in New Zealand with a couple of lovely ladies and more Middle Earth souvenirs than is reasonable.

You can find him on…